|

|

|

|

|

BY CYNTHIA ROZNOY

|

|

|

|

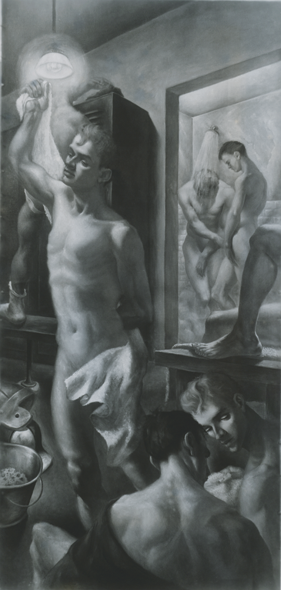

| Fig. 1: Milton Bellin, Physical Education, Study for mural, Teacher’s College, 1940. Gouache, tempera and chalk on brown paper, 68 x 30 inches. Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, Conn. |

The Federal Art Project (FAP), which opened in August 1935, was the visual arts division of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), created to provide economic relief during the Great Depression. In Connecticut, 169 artists produced nearly 5000 easel paintings, sculptures, and murals that were placed in public spaces such as hospitals, schools and libraries. Most of the art was not well preserved; much of it was lost and some destroyed as the Project ended abruptly in April 1943 when the United States became more involved in World War II. Today, approximately 1500 Connecticut FAP works have been located, among them several significant mural studies and paintings produced by Milton Bellin (1913–1997).

Nudity is rare in Connecticut FAP paintings. One, known only by reproduction, is Gilbert Banever’s Adam and Eve, an expulsion scene where the idealized figures lack anatomical detail and the male turns his back to the viewer. Swimmers in Joseph Schork’s Summer Frolic wear shorts or are concealed by opaque ocean waves. In contrast, frontal male nudity is the compositional focal point in Milton Bellin’s Physical Education (Fig. 1). This painting is also distinguished by an emphasis on male sensuality.

During a period marked by public prudery, paintings of nudes were not acceptable for public buildings. Edward Rowan, assistant director to the Public Works of Art Program (PWAP), which preceded the FAP, set the tone for all the federally supported art programs. He argued that while government artists should be given “the utmost freedom of expression,” the PWAP should “check up very carefully on the subject matter of each project…. Any artist who paints a nude should have his head examined.” 1 But Bellin didn’t need a therapist, he was confident in his subject choice and secure in the support of his patron.

Between 1937 and 1940 Milton Bellin was an artist-in-residence at the Teacher’s College of Connecticut, now Central Connecticut State University. The Class of 1937, as their class gift to the University, provided funds for five murals to be painted under the auspices of the WPA, who in turn provided the artist. As an undertaking of the FAP, Bellin assumed the residency.2 A brief history of Bellin’s work at the school identifies that the artist spent considerable time acquainting himself with student life. He frequently spoke to classes about the techniques employed in his work and often used students as models. He painted the murals on site, the main corridor of the Administration Building, making his work accessible and accepted. Bellin was a popular man on the campus. Thus sheltered, he may not have felt the need to self-censor nude subject matter. Indeed, the academic setting may have encouraged this direction; his depiction of male beauty had, after all been tolerated in history painting. That tolerance, however, had not wholly extended to depictions of contemporary life. So it was a brave artist who tested the waters with such imagery. Bellin apparently felt the time was right to confront restrictions regarding male nudity in the art of the everyday. Searching about, he would have found precedents for a shift in critical and popular reception of such subject matter.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Thomas Eakins, Swimming, 1885. Oil on canvas, 27⅜ x 36⅜ inches. Courtesy, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Tex. Purchased by the Friends of Art, Forth Worth Art Association, 1925; acquired by the Amon Carter Museum, 1990 from the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth through grants and donations from the Amon G. Carter Foundation, the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, the Annie Burnett and Charles Tandy Foundation, Capital Cities/ABC Foundation, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, The R.D. and Joan Dale Hubbard Foundation and the people of Fort Worth.

|

During the 1880s, prejudices and taboos around male nudity were challenged by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). An instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Eakins advocated the study of the live model and he emphasized the use of the nude. He produced a group of paintings that unabashedly presented male nudes in contemporary situations such as The Swimming Hole (Fig. 2), which represents the artist and five other naked men, his students and friends. Eakins’ efforts shifted the whole of art teaching in America; by the turn-of-the-twentieth-century life classes were sanctioned and the male nude emerged from his classical guise to be seen as a contemporary subject.3

Turn-of-the-century artistic interest in the contemporary male nude coincided with the rise of cultural interest in issues of masculinity and athleticism. There was a heightened rhetoric about gender due to the women’s movement and an increase in recreational activities as the result of President Theodore Roosevelt’s encouragement of swimming and boxing. Public baths, the precursor of modern swimming pools, were used for cleanliness but also, when the weather was hot and unbearable, used for recreation. The YMCA movement, in the United States since 1855, promoted the concept of physical health through sports. Men’s sporting places, locker rooms and showers provided artists with settings to develop group compositions and the opportunities to depict varieties of physiognomy.

Milton Bellin’s locker room scene has an early precursor in the art of Ash Can School artist George Bellows (1882–1925). In 1904 Bellows left Ohio to study art in New York. His short-term lodging at the Y inspired a series of lithographs: Business Men’s Class, Y.M.C.A. (1916), Shower-Bath (1917), and Business Men’s Bath (1923, all collection of Dr. Dorrance Kelly) (Fig. 3). An amusing “insider’s look,” the prints capture what Bellow’s described as “a humoresque.”

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: George Bellows, Business Men’s Bath, 1923. Lithograph, 11⅞ x 17. Collection of Dr. Dorrance Kelly.

|

The specificity of the shower, a scene that allowed the massing of many male nudes, became almost popular. Moreover, at a time when homosexuality was forbidden, depictions of the athletic life served as erotic imagery. In the early years of the twentieth century, modernist Charles Demuth (1883–1935) produced frank pictures of homosexual activity, signaling that the social climate, which had earlier been condemning, was changing.

The artist most notorious for provocative male imagery during the 1930s was Paul Cadmus (1904–1999), whose painting The Fleets In (1934) produced for the New York Public Works of Art Project, generated such a hullabaloo that it was hidden away for thirty years, rejected for its elements of drunkenness, prostitution, and homoeroticism. Cadmus and Bellin were contemporaries in Connecticut and most likely knew each other through friends such as artist James Daugherty, or through similar pursuits—they had a common interest in Renaissance figuration, they loved drawing the nude and both painted in egg tempera (then and now, not a common medium).

In 1933 Cadmus painted Y.M.C.A. Locker Room (Fig. 4), a scene that allowed him to express his respect for the classic depiction of the male. Cadmus’s interest in sculpted bodies and his emphasis on modeling of the human figure is evidenced in a view of fifteen men in various states of undress between the lockers and benches. There is a variety of interaction with open expression of male desire in this highly charged scene that documents cruising and seduction.

Bellin came under the influence of James Daugherty (1889–1974), whom he assisted with WPA murals for the Stamford Housing Project (now lost). Daugherty’s compositions of muscular male bodies reflected his study of Michelangelo and concurred with Bellin’s sensitivity to the well-defined, articulated muscles of the nude (developed during Bellin’s training at the Yale School of Art). Drawing from the nude model is considered an essential part of artistic training and Bellin continued the exercise at the Teacher’s College, using students of both sexes as his models.

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Paul Cadmus, Y.M.C.A. Locker Room, 1933. Oil on canvas, 19⅜ x 39¼ inches. Courtesy, John Axelrod.

|

|

Like his contemporaries, Bellin framed his appreciation of the male body within the larger context of sports and athleticism. In addition to demonstrating the aesthetic of ideal form it provided a forum to show varieties of attitudes and poses. The artist began his painting with conté drawings of partial figures. He then created a full-size preliminary drawing with all compositional and lighting elements in place. These works on paper are in the Central Connecticut State University collection, though the finished painting has not been located. It is known by photograph documentation for the FAP and by a posed photograph of the artist standing in front of the painting (also in the CCSU collection) (Fig. 5).

There are three significant differences between Bellin’s nudes and classical renditions: the provocative pose and the emotive mein of the figures; the veiled, perhaps furtive interactions between the figures; and a voyeuristic sense the viewer experiences when contemplating the work. With this painting Bellin shifts away from his traditional training and classical rendition and moves to a provocative appreciation of the male form that is just emerging in American art. By the 1930s, the nude had gained value as the carrier of male identity, particularly gay identity. Physical Fitness fits this new model as the central figure is displayed as an erotic object for the viewer; an introduction to the homosexual theme. It may be a gym setting, but Bellin subverts the conventional stereotype of the athlete here—he is not a brawny, loud fellow but an inward-seeing, human object of beauty.

Bellin lets us into a world that was seldom seen—steamy locker rooms and showers with the smell of sweat and soap where homosexuality is exhibited in triumphant poses. The artist gives an honest and beautiful view of eroticism as he re-introduces the male nude in a modern, different way.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: The artist working on the painting, Physical Education, which has not been recovered.

|

We have no clues identifying Bellin’s instigations and goals for this work. Physical Fitness is singular in Bellin’s oeuvre; he produced more than sixty works for the Federal Art Project, among them portraits, landscapes, and urban/industrial scenes. Was he using the work to express sexuality? None of Bellin’s other artistic output supports this reading. There were no other images of nudity; there are no notebooks or journals that provide insight. Did Bellin set out to shock his patron, the government, with male sexual exhibition and exposure? It is unlikely he did.

Critical and audience response to this work was mostly undocumented. Contemporary accounts in The Recorder, an in-house Teacher’s College publication identified only that Bellin was at work on a mural series; a year later another account records an exhibition. There was no critical review. The lack of contemporary commentary does not allow us to determine the school’s response to the work.

It may be that one of Bellin’s goals with this mural was to conquer the divide between traditional art and contemporary life using themes and subjects drawn from popular culture. The melodramatically painted Physical Fitness has much in common with the distinctive look of 1930s film noir with its low-key lighting and unbalanced compositions. Bellin uses the moodiness of film noir black-and-white films to supplement the potential for narrative. The viewer/voyeur has access to a pseudo reality that fulfills his/her needs for fantasy and subliminal desire.6

German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, Olympia, may also have provided source material. Released in the United States the next year, the film included many comparisons of Nazi athletes and ancient Greek sculptures. Bellin’s shaping of form and the voyeuristic component of watching closely match the Riefenstahl aesthetic.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Charles Atlas advertisement, “Hey Skinny! Your Ribs Are Showing.” Courtesy, Charles Atlas Ltd., New York, NY.

|

In 1929 the Olympic swimming champion Johnny Weissmuller signed with BVD to be a model and representative, promoting swimwear. Three years later he starred in Tarzan the Ape Man, which launched a series of Tarzan movies that reached millions. Bellin, no doubt, knew of Tarzan, this was after all, an era when tens of millions of American’s attended movies weekly.

Sport itself must have impacted the work. One sport, particularly gaining popularity at the time was bodybuilding. Men worked diligently to achieve muscled bodies with detailed modeling of sinews and muscles. Charles Atlas, born Angelo Siciliano, was an Italian immigrant whose life story inspired many young men to the sport. Atlas made a legend from an experience he’d had as a teenager on a Coney Island beach when a bully had kicked sand in his face (Fig. 6). Eager to stand up to such intimidation, Atlas developed and sold “Dynamic Tension” mail-order courses to generations of boys who wished to face down their own bullies.

Nudity as a lifestyle choice was part of the Connecticut public conscious at this time.7 Solair, New England’s first nudist camp, was close at hand, about fifty miles from the Teachers’ College Campus in Woodstock, Connecticut. Established in 1935, it manifested popular interest in the nudist movement, which had developed in America during the progressive era, 1890–1920.8

While the norms of sport and contestants promulgated in popular imagery inform Bellin’s work, the scene violates commonly accepted conventions of masculinity for that time. The lack of critical discourse regarding the painting prohibits our understanding of audience reception. Its large scale confronts the viewer with its subject matter so the impact of facing a life-size nude male is dramatic. Its open expression of male sensuality is unusual. So is the lack of public controversy. Patrons of this work include a college and the government, not typical proponents of sexual imagery.

As a gay theme, this work is rare in FAP art and in Bellin’s oeuvre. Physical Fitness offers an interpretive ambiguity that resists better understanding until more about the artist and his motivations are known.

|

|

|

|

|

Dr. Cynthia Roznoy, Mattatuck Museum curator, is currently at work on an exhibition celebrating the centennial anniversary of the museum’s first art exhibit.

1. Quoted in Townsend Luddington, ed., A Modern Mosaic: Art: Modernism in the United States (Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 232. 2. See “History: Bellin-WPA Murals” a handout provided by the Student Center of Central Connecticut State University. Bellin painted 5 murals on site in the corridor of the administration building. Though no reason for their removal is given, the murals were carted off sometime around 1950. Found in the administration building attic in the 1970s, the murals were restored and installed in the Student Center in 2000. 3. Eakins contemporaries also produced male nude works including, for example, William Morris Hunt, The Bathers (1877, Worcester Art Museum); J. Alden Weir, Study of a Male Nude; Albert Thayer, Male Nude (ca. 1878, Fort Worth Art Center). 4. See Lauris Mason assisted by Joan Ludman, The Lithographs of George Bellows: A Catalogue Raisonné (Millwood, NY: KTO Press, 1977). 5. 6. See James Naremore, “American Film Noir,” Film Quarterly (Winter 1995–1996). 7. The nude theatrical performance The Girl from Childs made headlines in Hartford Courant (April 16, 1935) as did Elysia, advertised at an “Authentic Nudist Film” (Hartford Courant, May 13, 1934). Movie houses in Hartford, Stafford, and Willimantic were closed and the film withdrawn after public protests (Hartford Courant, May 15, June 20, July 13, 1934). Other news included “Winter Lyme Nudist Colony, Number 16, Farm Census Shows” (February 16, 1935) and “Nudists Are Told Cult is Raised Up by God (August 23, 1937). 8. See Lindsay A. Mazziotto, Trading Clothes for Optimism: A Comparison of the German and American Nudist Movement (masters thesis, Simmons College, Massachusetts, 2011).

An exhibition featuring 70 of the state’s FAP works is presented at the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Connecticut, through February 6, 2013. This article is taken from an essay in Art for Everyone: The Federal Art Project in Connecticut (Wesleyan University Press, 2013). This essay is part of a broader study documenting Connecticut artists and their work for the Federal Art Project. Thanks go to Deborah Edwards, Mark Jones, and Amy Trout, my colleagues on that undertaking.

|

|