A Cutwork Tree of Life in the Manner of Hannah Cohoon

Alayered cutwork Tree of Life, discovered at a Connecticut antiques show in the booth of the late Frank Ganci, presented an intriguing puzzle when it first came to light in 1980 (Figs. 1, 1a). Upon its removal from a non-original frame, the cutwork exhibited legitimate signs of age. Of paramount interest was its obvious resemblance in silhouette to the design of The Tree of Life painted by Hannah Cohoon (1788–1864) at the Hancock, Massachusetts, Shaker community in 1854 (Fig. 2). The question is, does this cutwork represent a major Shaker discovery or a twentieth-century copy based on the original work?

|

Fig. 1: Cutwork tree of life, Possibly Hancock, Massachusetts or New Lebanon, New York, ca. 1850–1875. Cut paper and watercolor on paper, 8-1/2 x 10-15⁄16 inches. Private collection. Photography by Gavin Ashworth, courtesy of David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles. |

| |

| Fig. 1a: Detail of Cutwork tree of life, pictured in figure 1. Private collection. Photography by Gavin Ashworth, courtesy of David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles. |

Any analysis of the cutwork picture must be measured within the known history of Cohoon’s Tree of Life. Today a widely recognized icon of American art and a symbol for all things Shaker, Cohoon’s image was unknown to the “outside world” until it was revealed to Faith Andrews and Edward Deming Andrews by Sister Alice Smith at Hancock not later than 1931.1 It was one of four paintings signed and dated by Cohoon that the Andrewses acquired from the Hancock Shakers, along with gift drawings by other artists.2 These gift drawings were part of the first major museum exhibition of Shaker material, which was held at the Whitney Museum in 1935.3 It was not until ten years later that a small black-and-white reproduction of Cohoon’s Tree of Life appeared in an article by Edward Deming Andrews in Antiques (December 1945). The image was used by the Andrewses on the cover of two of their books—Visions of the Heavenly Sphere (1969) and Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life (1975)—and has since been widely disseminated.4 The Andrews sold much of their collection, including the Cohoon paintings, to the Hancock Shaker Village after it was established as a museum in 1960.

Shaker gift drawings originated during an intense religious revival that began in 1837 and continued through the 1850s, when gifts from the spirit world in the form of verbal messages, songs, dances, and visions were revealed to the Shakers by mediums known as “instruments.” Some two hundred gift drawings are extant, almost all of them from the Shaker communities of Hancock and New Lebanon, New York; it has been suggested that hundreds more have been lost.5 After the revival waned, many Shakers seem to have been embarrassed by the emotional excesses and mystical expressions of the period. At Hancock, most of the large colorful pictures were put away in cupboards and forgotten.

|

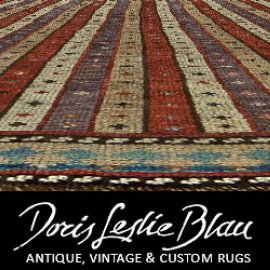

Fig. 2: Hannah Cohoon (1788-1864), The Tree of Life, Hancock, Massachusetts, 1854. Ink and tempera on paper, 18-1/8 x 23-5⁄16 inches. Courtesy of Andrews Collection, Hancock Shaker Village. |

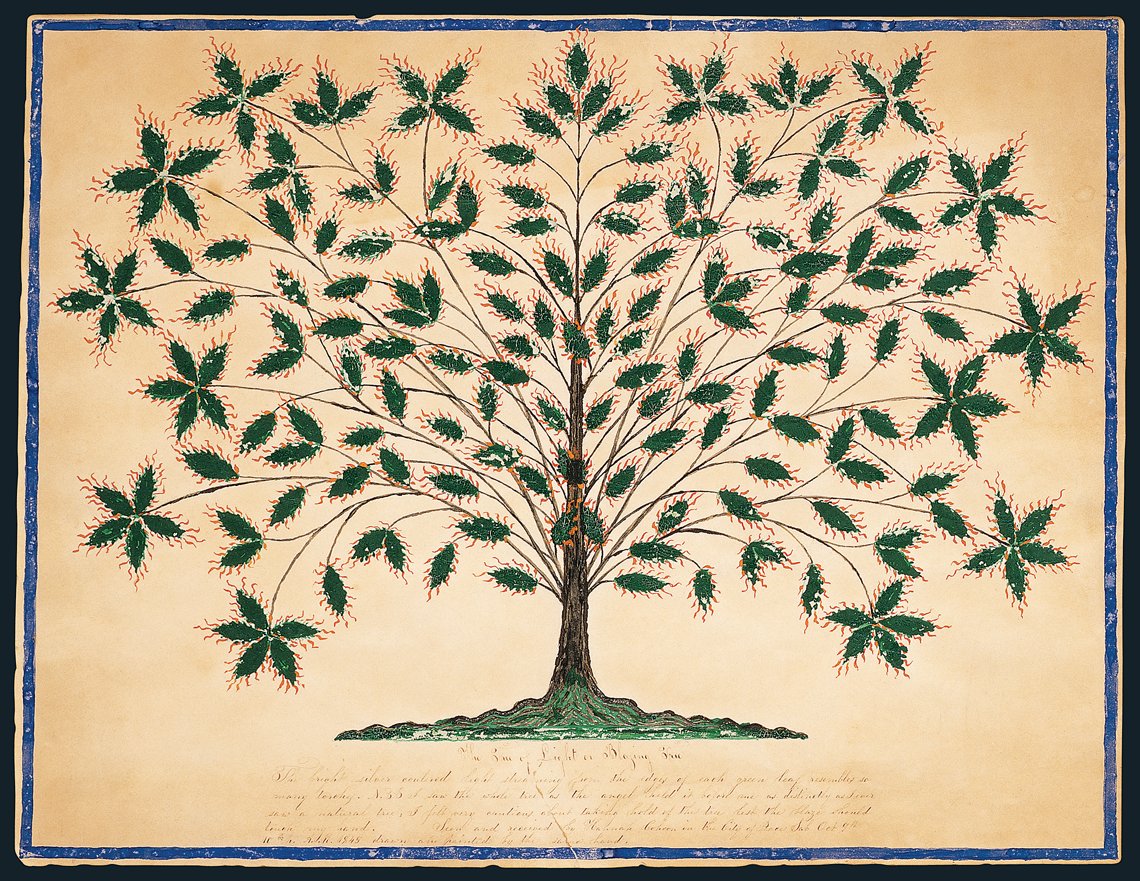

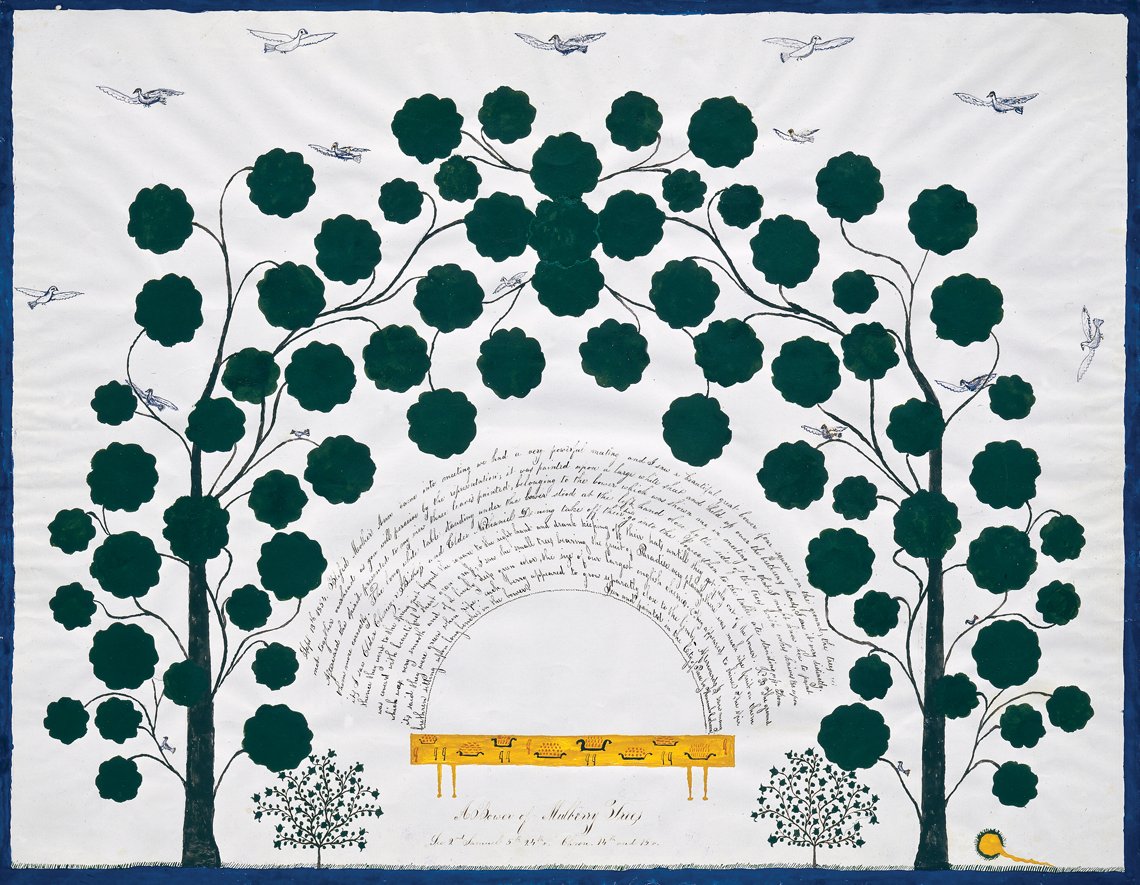

The artists who worked at Hancock—Joseph Wicker, Hannah Cohoon, and Polly Collins—all favored imagery drawn from nature, especially trees. For the Shakers, the Tree of Life was an instantly recognizable symbol, celebrated in sermons, gift songs, and in their early history as a representation of the unity of the Shaker Church. Cohoon’s Tree of Light or Blazing Tree (1845) and The Tree of Life (1854) feature a large central tree boldly rendered in red and green to produce a dazzling optical effect; A Bower of Mulberry Trees (1854) is dominated by the curving branches of trees that form an arch over a long Shaker table set for a feast (Figs. 3, 4). Cohoon’s latest and simplest composition, Basket of Apples (1856), depicts not the tree but its fruit. When a fifth painting by Cohoon, a second version of The Tree of Light or Blazing Tree, was discovered in 1996, it was evidence that Cohoon’s output was larger than the four previously known paintings, and that she was inclined to repeat her designs.6

Hannah Cohoon was a woman of twenty-nine and the mother of two young children when she entered the Hancock community in 1817. Although little is known of her early life or education,7 she may have been instructed in watercolor painting and surely would have learned needlework skills, which were considered essential for every young woman. Cohoon’s great single-image paintings of trees suggest a thorough knowledge of embroidery, appliqué, and quilting techniques. The Tree of Life as a design motif would have been familiar to Hannah Cohoon from any number of sources, from imported textiles to family records. A Shaker source may have been the large bannerlike painting of a tree surrounded by mysterious calligraphy that was made in 1844 by Elder Joseph Wicker of Hancock.8 It is tempting to suggest that Wicker’s rather clumsy depiction established the Tree of Life as a motif that Cohoon brilliantly transmuted into masterworks of art.

|

Fig. 3: Hannah Cohoon (1788-1864), Gift Drawing: The Tree of Light or Blazing Tree, Hancock, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, 1845. Ink, pencil, and gouache on paper, 16 x 20-7/8 inches. Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York, promised gift of Ralph Esmerian (P2.1997.1). Photo courtesy Sotheby’s, New York. |

The cutwork Tree of Life has remained unstudied for the past thirty years. Scientific analysis not readily available in the early 1980s prompted the present study. Logically, one of three scenarios must explain the authorship of the cutwork Tree of Life. It may be the work of Hannah Cohoon; it may have been made by another unidentified Shaker based on Cohoon’s painting; or it could have been created after 1931, copied from Cohoon’s Tree of Life.

When paper conservator Theresa Fairbanks Harris examined the cutwork in 2010, she observed that it does not appear to have ever been tampered with or conserved, and that the collaged elements had been connected long enough to show normal signs of age such as the discoloration of the cutout tree and the fading of the mounting paper. She concluded that it was probably made in the third quarter of the nineteenth century,9 a period that encompasses Cohoon’s final years and the decade following her death.

Scientific analysis by Kate Payne de Chavez and Leslie Paisley at the Williamstown Art Conservation Center revealed that no modern materials were used in the manufacture of the cutwork. Through polarized light microscopy (PLM) the papers were found to contain cotton and linen fibers consistent with the period of 1850–1900. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) identified the green pigment used to color the mounting paper as either chrome oxide green (Cr203) or viridian, the hydrated oxide of chromium. These were pigments readily available by 1849.10 Chrome oxide green was identified in Hannah Cohoon’s A Bower of Mulberry Trees (fig. 4) when it was analyzed by the Williamstown Art Conservation Center in 1992. This same type of green paint was identified by Susan L. Buck as the original surface treatment of a Shaker bed probably made at New Lebanon.11

|

Fig. 4: Hannah Cohoon (1788-1864), A Bower of Mulberry Trees, Hancock, Massachusetts,1854. Ink and tempera on paper, 18-1/8 x 23-1⁄16 inches. Courtesy of Andrews Collection, Hancock Shaker Village. |

The verso of the cutout tree bears pencil lines, indicating that it was not cut freehand. A cotton/linen fibered, smooth surfaced beige paper was used for the cutout tree. Its color could be the result of toning, water damage, a coating, or natural aging, or a combination of all four factors. The recto is mottled with a discoloration frequently seen on artwork framed in direct contact with glass. A medium weight, slightly textured, cotton/linen fibered wove paper was used for the mounting paper. It showed no signs of having been trimmed down after the application of the green coating, which occurred after the paper was made and before the collage was attached. Subsequent water damage to the recto has moved the green color from the recto to the verso. Deep horizontal creases, one on the top and two on the bottom, occurred after the sheet was coated. With two exceptions—a missing leaf and the positioning of a branch—the cutout tree is in the exact pattern of Hannah Cohoon’s Tree of Life but executed in a smaller scale; in both compositions the image of the tree nearly fills the entire sheet.

|  | |

Figs. 5, 5a: Polly Jane Reed (1818-1881), Leaf-shaped gift drawing to Rufus Bishop, Mount Lebanon, New York, 1845. Ink and watercolor on cut paper with one side coated with green pigment, 8-3/4 x 4-3/8 inches. Courtesy of Miller Collection, Hancock Shaker Village. | ||

Although layered cutwork is frequently associated with the Pennsylvania-German technique of scherenschnitte, variations were produced in many other parts of the United States, from Maine to Missouri. A specialized form of cutwork was produced by the Shakers in the context of their gift drawings. Numerous small “gifts” were fashioned from cutwork in the shape of leaves, hearts, and circles with inscriptions and drawings executed in pen and ink. These are analogous to the friendship tokens and rewards of merit that were frequently exchanged among contemporary non-Shakers. A precedent for applying a green coating to paper is demonstrated by a Shaker gift drawing cut in the shape of a leaf (Figs. 5, 5a), one of several made by Polly Jane Reed at New Lebanon, New York, in 1844 and 1845.12 Like the mounting paper of the Tree of Life cutwork, this leaf was coated with green pigment on just one side.

The condition and general appearance of the cutwork Tree of Life is quite different from the majority of Shaker works on paper, which were stored unframed, in dry, dark places that preserved the freshness of their colors and whiteness of their paper. The cutwork was subjected to contact with moisture and lengthy exposure to sunlight, and its upper and lower margins were folded in the course of being reframed. The degree of fading is best illustrated by the witness mark left by one of the leaves shown in figure 1a. Also revealed in this unexposed area is a hint of the original appearance of the green background color. Using this area of hidden preserved color as a sample, and one brighter spot of the cutout tree, photographer Gavin Ashworth digitally recreated how this work may have appeared when it was new, without distracting creases, discolorations, or fading (Fig. 6). As depicted in the digital facsimile, the green background exhibits a vibrancy and tone that is quite similar in appearance to the greens found in the well-preserved paintings by Hannah Cohoon and the leaf-shaped gift drawings by Polly Jane Reed. Without the distracting blemishes, the boldness of the cutwork’s pattern is fully revealed.

|

Fig. 6: Digital facsimile of original appearance of cutwork tree of life by Gavin Ashworth, courtesy of David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles. |

Scientific analysis has established that the cutwork Tree of Life was made from materials available in the second half of the nineteenth-century. The green pigment, either chrome oxide green or viridian, was specifically used by Hannah Cohoon in her paintings and by other Shaker craftsmen of the period to paint furniture. Another characteristic shared by the cutwork and Cohoon’s paintings is the use of preparatory pencil guidelines.13

Without her signature, an inscription, provenance, or other documentation, insufficient proof exists to warrant an attribution of the cutwork Tree of Life to Hannah Cohoon. Since her Tree of Life was unknown outside the Shaker world prior to 1931 (and not widely reproduced until the 1960s), it is not unreasonable to suggest that the cutwork was created by a Shaker with access to Cohoon’s painting. Perhaps it was Polly Collins (1808–1884), another documented maker of gift drawings at Hancock who was Cohoon’s younger contemporary. Another candidate could be Polly Jane Reed (1818–1881), who was responsible for the heart and leaf gift drawings at New Lebanon. The New Lebanon and Hancock Shaker communities were only a few miles apart, and their residents often exchanged visits, during which Reed could have seen Cohoon’s paintings.

In the end we are left with an enigma. Is the cutwork Tree of Life an unsigned work attributable to Hannah Cohoon, Polly Collins, Polly Jane Reed, or another yet unidentified Shaker, or is it a copy inexplicably fashioned from period materials for yet unknown reasons? Perhaps future research or the advent of new technologies will yield a conclusive answer.

1. Mario S. De Pillis and Christian Goodwillie, Gather Up the Fragments: The Andrews Shaker Collection (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 79.

2. The term “gift drawing,” proposed by Daniel W. Patterson in his comprehensive study Gift Drawing and Gift Song (Sabbathday Lake, ME: The United Society of Shakers, 1983), has largely replaced Andrewses’ term “inspirational drawings,” although gift drawing is perhaps too restrictive, because the works range from monochrome pen-and-ink drawings to colorful watercolor paintings.

3. The 16-page catalog had no illustrations other than a woodcut based on Hannah Cohoon’s Bower of Mulberry Trees on the cover.

4. For the use of Cohoon’s Tree of Life image by Shaker-related enterprises, see Stephen Bowe and Peter Richmond, Selling Shaker: The Commodification of Shaker Design in the Twentieth Century (Liverpool, GB: Liverpool University Press, 2007), 61–62, notes 136, 137.

5. Edward D. Andrews and Faith Andrews, Visions of the Heavenly Sphere: A Study in Shaker Religious Art (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1969) includes a checklist of 113 works; Patterson in Gift Drawing and Gift Song, (1983) added 79 more; several have since been discovered.

6. The second version of the Blazing Tree was discovered along with another Hancock painting by Polly Collins in the backing of an old picture frame. Its less than pristine condition when found speaks to ownership outside the reverent hands of the Shakers. Like the cutwork, it had suffered the vagaries of unknown framing campaigns and the damaging effects of environment and handling.

7. See Ruth Wolfe, “Hannah Cohoon (1788-1864),” in Jean Lipman and Tom Armstrong, eds., American Folk Painters of Three Centuries (New York: Hudson Hills/Whitney Museum of American Art, 1980), 58–63.

8. Illustrated in Patterson, 56, and on the cover of France Morin, Heavenly Visions: Shaker Gift Drawings and Gift Songs (New York: The Drawing Center / Los Angeles: UCLA Hammer Museum / Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

9. Report by Theresa Fairbanks Harris dated October 21, 2010.

10. Report by Kate Payne de Chavez dated Nov. 1, 2011, and report by Leslie Paisley dated Nov. 17, 2011.

11. Susan L. Buck, “Interpreting Paint and Finish Evidence on the Mount Lebanon Shaker Collection,” in Timothy D. Rieman, Shaker, The Art of Craftsmanship: The Mount Lebanon Collection (Alexandria, VA: Art Services International, 1995), 50-51. The Shakers’ Millennial Laws, revised in October 1845, mandated that all bedsteads be painted green.

12. For illustrations, see Andrews, Visions of the Heavenly Sphere, figs. 5, 6, 18; Sharon Duane Koomler, Expanding the Vision: Gift Drawings in the Eric J. Maffei Collection (Pittsfield, MA: Hancock Shaker Village, nd), unpaginated; Koomler, Seen and Received: The Shakers’ Private Art (Pittsfield, MA: Hancock Shaker Village, 2000), unpaginated; Morin, 63, ill. 7.

13. Sally M. Promey, “Resurrecting Vision: The Pictorial Imagination of Shaker Revival,” in Morin, 76.

|

A collector since childhood, David A. Schorsch has been dealing in American antiques for thirty-five years. Since 1995 he has been affiliated with Eileen M. Smiles in Woodbury, Connecticut. Ruth Wolfe is author of “Hannah Cohoon (1788–1864)” in American Folk Painters of Three Centuries (1980).

This article was originally published in the 13th Anniversary (Spring/Summer 2013) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.