Specimens of Taste and Skill

New England Hearth Rugs, 1800–1850

The use of both factory woven and homemade hearth rugs coincides with the increasing use of carpeting in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as people sought to protect their investments in woven floor coverings and participate in a growing fashion trend. Homeowners discovered that carpets became worn and developed holes at that spot in front of the fireplace where people gathered to warm themselves. As a result, protective hearth rugs soon became a standard component in rooms with room-sized carpets. Placed over the carpet in wintertime and over the hearthstone in summer, these rugs added a powerful ornamental feature to the domestic setting throughout the year.

Although some now question the original role of these highly decorative rugs, by 1828 Noah Webster had defined their function as being “particularly for covering the carpet before the fireplace.” Similarly, in 1835 John Claudius Loudon stated that “their use is obvious, in saving the carpets from becoming worn by the constant movement of persons near the fire.”1 In 1843, the Boston author Lemuel Shattuck included thirty yards of carpet and one hearth rug in his lists of “necessary furniture” for both parlors and sitting rooms.2 Similarly, in 1844 Thomas Webster confirmed the dual function of hearth rugs as being “to save the carpet near the fire, where it is most liable to be worn, and likewise to afford greater warmth and softness to the feet at that place” 3 (Figs 1, 2). None of these authors mentions the pictorial qualities and exquisite needlework that make these rugs so highly prized today. It was their protective function that defined them in their own time.

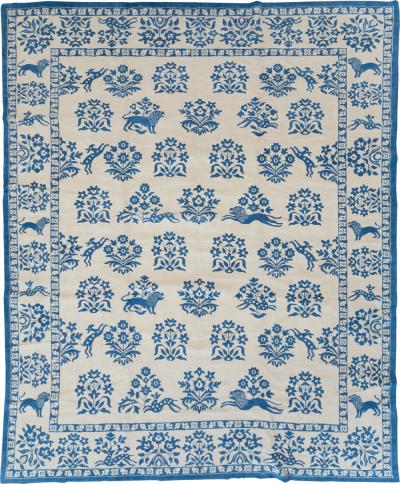

It is difficult for us to understand the aesthetic sensibility that governed the visual relationship between pictorial hearth rugs and the larger carpet upon which they were displayed. It may be that having some color harmony was all that was required: landscape scenes, bowls of fruit and flowers, arrangements of flowers and shells, exotic animals, and household pets all seem to have been popular images on hearth rugs, while carpets usually displayed repeating naturalistic or geometric patterns.

Newspaper advertisements of carpet dealers document the availability of both English and American Brussells, Kidderminster, Imperial, and Wilton hearth rugs, with such desirable qualities as “cheap,” “prime,” “of superior quality,” “new and beautiful patterns,” and “in great variety” as well as, much more rarely, “to match.” Occasionally, we find descriptive specifications such as those for the twelve “Brussells Rugs” of “the Hare and Landscape pattern” that the Boston carpet dealer and looking glass manufacturer John Doggett ordered on April 11, 1827.4

In their encyclopedias, both Loudon and Webster acknowledged that commercially made hearth rugs varied considerably in style and price; they also pointed out that it was neither difficult nor expensive to make them at home. Many women found satisfaction in exploring the creative possibilities in embellishing a moderately sized rectangle of cloth with a picture made of applied strips of cloth or embroidered woolen yarn and in the process creating a useful article of household furnishing.

Although most girls learned basic sewing skills at home, an undefined kind of “rug work” was taught in some female academies as early as 1806. Some girls who had received this instruction submitted their rugs for exhibition at agricultural fairs and on occasion received prizes. In 1824, according to the Columbian Centinel, the highest premium, $5, at the Brighton Cattle Show was awarded to the Misses Scott who had studied at the Academy of the Misses Clark in Boston, and in 1826, the Haverhill Gazette & Essex Patriot reported that at the Essex County Cattle Show in Danvers a $4 premium was given to the ten- and twelve-year- old Johnson sisters for their “very neat hearth rug wrought at Mrs. Page’s School” in Newburyport.

Among the various handmade items exhibited by women and girls for cash prizes at New England agricultural fairs and cattle shows before1850, hearth rugs were increasingly the largest category of “domestic manufactures” submitted. At the annual exhibition of the Hartford County Agricultural Society in 1820, the judges reported “that scarcely anything submitted to their examination denotes so rapid an improvement in taste and domestic industry as the hearth rugs—those which were this year exhibited, displayed an elegance both in their design and execution, which in articles of that kind is rarely met with.” 5

Lacking any sophisticated vocabulary of aesthetic description, the judges praised the winning entries for their beauty, durability, and economical use of materials. Described as everything from “handsome” to “fashionable“ to “beautifully worked,” and “fancy and durable,” we are often left to wonder what they actually looked like. As reported in the October 1826 New England Farmer, at the Hillsborough County Cattle Show at Wilton, New Hampshire, judges declared that some of the hearth rugs “were curiously wrought with flowers or landscape figures and as they unite utility with beauty, will be quite as ornamental to a farmer’s parlour as a gilt framed painting or embroidery.”

Economy was always prized by thrifty New Englanders. At the Essex County show in November of 1824, the New England Farmer reported that a Mrs. Robert Piper of Newburyport received $3 for “an ingenious and handsome hearth rug,” the materials for which cost only 50 cents. Considering that a rug could be worked on a leftover piece of mattress ticking or linen sheeting, using leftover yarn in its embroidered embellishment, it is indeed clear how such a rug could be economical.

As early as 1822, braided hearth rugs were exhibited at the Plymouth County, Massachusetts, Agricultural Society fair.6 More braided rugs were exhibited in 1827, but the technique was seldom featured thereafter. It’s unclear why braided rugs were considered unworthy of exhibition but they continue to be made to the present day.

Many of the prize-winning rugs were described as “worked,” meaning that they were embroidered in wool with small loops resembling those of a woven Brussels carpet covering the entire surface of the rug. Today the technique is called “yarn sewn.” Another kind of rug, known today as “shirred,” was described by J. C. Loudon in his 1835 Encyclopedia as a “kind of cheap hearth rug…[with] a remarkably rich, warm, and massive appearance,” easily made at home of half-inch strips of cloth, cut three or four inches long, doubled, and sewn at the fold onto a piece of strong cloth with the strips arranged into “some kind of pattern” (Fig. 3; Detail of Figure 4a). Arabella Stebbins (Sheldon) Wells of Deerfield, Massachusetts, made two rugs in this technique, depicting both her family home, the Sheldon homestead (fig. 3) and the nearby “Old Indian House” (Fig. 4), which was already famous for its role in the 1704 raid on the town. Mrs. Wells may have relied on her own skills to draw the pattern or she may have utilized an illustration (Fig. 5) to aid her depictions of scale and perspective.

Some rug designs illustrated real life situations. Apparently among the most popular was the very familiar image of a dog or cat curled up on a rug before the fire. Perhaps the most well-known images of domestic animals on rugs are those in the famous “Caswell carpet.” Three of the squares that comprise the carpet contain either puppies (Fig. 6) or cats lying on warp-faced striped or “Venetian” carpets. Whether borrowed from a published illustration (Fig. 6a) or a manufactured hearth rug, a similar image of puppies is the centerpiece of a handsome hearth rug (Fig. 7) by a former needlework instructor, Mrs. Elizabeth Williams of Deerfield, for which she received a gratuity of $1 at the Brighton, Massachusetts, cattle show in 1825.7

The image of a dog or cat curled up in front of the fire seems to have quickly become something of a cliché, for when John Doggett ordered fifty Imperial Wilton hearth rugs in 1828, he specified “we do not wish Dogs or pointers” on them. The next fall, when he placed an order for rugs with Charles Wright in Kidderminster, requesting rugs with “all high and rich colors and a good proportion scarlet grounds—the patterns we shall leave to your judgment,” he again specified, “we do not wish any animals.” 8

There were divergent opinions as to the rendering of images. In 1832 the Hillsborough, New Hampshire, county fair judges felt “Some [ladies], it is true, will work with more taste than others; but if mere utility be the only question, it matters not whether the dog or sheep be perfect and distinct, or whether its species be unfortunately equivocal.” 9 Others believed that realism mattered. In the October 14, 1843, Maine Cultivator and Hallowell Gazette recorded that a lady from Pittston, Maine, was praised for a hearth rug with “scenic representation in needlework of houses, fields, streams, men, women, cattle, sheep, &c. &c. [that] exhibited great skill and labor.”

Hearth rug designs were frequently borrowed from book or magazine illustrations. In Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1839, Miss Abigail Smith of Fitchburg was awarded a prize of $2 for her hearth rug depicting the “Colossal Statue of Peter the Great,” as illustrated in The Penny Magazine (Fig. 8). In 1842 “a worsted rug containing 11,000 stitches, wrought by Mrs. J. Trask Woodbury, of Acton, [Maine]” depicted the “Cats and Monkey at Law” from the fables of La Fontaine, according to a report in the Portsmouth Journal of Literature and Politics of January 15, 1842. Neither of these rugs has been found and collectors are urged to keep an eye out for them.

Illustrated broadsides and newspaper advertisements for the “Celebrated Menagerie and Aviary” from New York, in 1834–1835, were the inspiration for hearth rugs depicting exotic animals (Fig. 9). Many of the woodcuts themselves derived from Thomas Bewick’s (1753–1828) History of Quadrupeds, (London, 1790) or Art of Nature (Philadelphia, 1810).10 During their extensive tour, in 1835 the animals were displayed on June 20 at Winthrop, Maine, on July 4 at Lowell, Massachusetts, and in many other cities. The big cats captured the attention of the now unknown women who used images from the tiny woodcuts as central motifs in their rugs (Figs. 10, 12). The stance of each animal and the flow of its tail are closely related to the menagerie’s advertising (Figs. 11, 13).

Such hearth rugs must have dominated sparsely furnished parlors. Susan Dickinson, sister-in-law of the poet Emily Dickinson, remembered an evening when at a secret meeting of the Poetry of Motion Society in Amherst, Massachusetts, a group of young people removed a hearth rug “to relieve the dancing toes from clumsy entanglement in the fringe.” The rug, ornamented with a lion, “a big brown fellow, set off by a vague green background,” was restored after the dance. In their haste the girls had “completely reversed [the rug], so that his majestic tail turned up where, by precedent, it should have been turned down, and all his members were topsy turvy!” The evening’s entertainment was revealed when the observant mother entered the room the next morning and shrieked, “Why girls! Girls! What has happened? The lion’s tail is upside down!” 11

As the century progressed, new methods of rug making were introduced, most notably hooking. Since many of these rugs were very durable, supply soon exceeded demand and small rugs began to be used at entryways and beneath washstands, and to warm feet at bedsides. The special function of hearth rugs was forgotten as “scatter rugs” appeared everywhere.

In all areas of women’s fancy work, there was an increasing variety of articles produced, many of which defied the concept of usefulness. Still, women have always been proud of their handwork and eager to display it. In 1838, the New England Farmer reported that the Worcester Cattle Show hall “was filled with specimens of domestic manufactures, such as hearth rugs, carpets, counterpanes, and a hundred nameless, useful and fancy articles, the handy work of the thrifty housewives and their daughters.12 Today the best of these items are considered folk art and outstanding examples bring high prices in the marketplace.

Jane C. Nylander is president emerita of Historic New England. A well-known author, she has also served as director of Strawbery Banke Museum and curator of textiles at Old Sturbridge Village.

1. J. C. Loudon, Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture (new edition, 1835), paragraph 686.

2. Lemuel Shattuck, The Domestic Book Keeper and Practical Economist (Boston, 1843), 26.

3. Thomas Webster, An Encyclopedia of Domestic Economy (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1844), paragraph 1072.

4. April 11, 1827, John Doggett & Co., Letterbook 1825–1829, Collection 330, 64x11, The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

5. New England Farmer, October 17, 1820.

6. New England Farmer, October 19, 1822.

7. For a biography of Mrs. Williams, see Leslie L. Rounds, I My Needle Ply With Skill; Maine Schoolgirl Needlework of the Federal Era (Saco, Maine: Dyer Library and Saco Museum, 2013).

8. October 9, 1828. John Doggett & Co., Letterbook 1825–1829, Collection 330, 64x11. The Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

9. “Report of the Committee on Fancy Articles” Hillsborough [NH] Agricultural Fair, Farmer’s Cabinet, October 12, 1832.

10. Fine examples of the broadside are in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society at Worcester, Massachusetts and the Shelburne Museum, Vt.

11. Susan H. Dickinson, Two Generations of Society: Essays on Amherst’s History (Amherst, Mass.: The Vista Trust, 1978), 179.

12. New England Farmer, October 17, 1838, 118.