|

|

|

|

|

|

by Sarah Lees

|

|

|

|

|

Both artists had been academically trained, Degas at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and Picasso initially under the instruction of his father, who taught drawing, and then at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Barcelona. A traditional approach informs many of their early works: Their self-portraits (Figs. 1, 2) both take a standard bust-length format, and the strong, dramatic lighting in Picasso’s depiction suggests that he drew inspiration from formal studio portraiture. The sitter’s casual attitude and the roughness of the paint handling, however, give the work a striking immediacy. The fourteen-year-old artist stares directly outward yet seems uncertain of himself, a pose that reflects his still-adolescent status. Degas, who was about twenty-three or twenty-four when he painted his self-portrait, presents himself with a similarly guarded expression, his eyes veiled by the shadow of his hat, though his identity as an artist is more clearly established by the roughly sketched smock and salmon-colored scarf. |

|

|

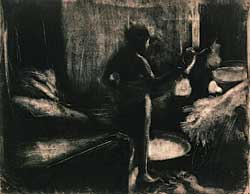

Picasso spent much of the year 1901 in Paris, where he rented a room in Montmartre and immersed himself in the neighborhood’s artistic community. The Blue Room (Fig. 3) depicts his quarters on the boulevard de Clichy, the simply furnished space serving as a backdrop to a model posed in a shallow tub, in the process of bathing. A well-known poster by Toulouse-Lautrec depicting the cabaret performer May Milton appears on the wall, clearly indicating one of the types of art — as well as the types of entertainment — that interested Picasso at the time. In a more subtle way, the model’s pose also echoes numerous bathers that Degas depicted in the 1890s, their awkward, twisting gestures mirrored in the sharply angled neck and shoulders of Picasso’s figure. An earlier work by Degas, the unusually large monotype The Tub (Fig. 4), shows the same sort of room as that depicted by Picasso in a similar state of casual disorder, the same type of tub, and a model equally absorbed in the solitary task of her toilette. This print was in a private collection by the early twentieth century, so Picasso may have known it or seen a reproduction of it. |

|

|

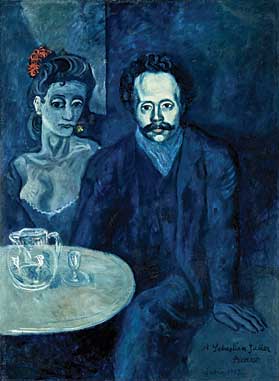

Between 1900 and 1904, Picasso sketched and painted numerous images set in the cafés and cabarets that he and his bohemian friends frequented both in Barcelona and in Paris. His images focused not only on the performers but also on the clientele, figures for which Picasso often asked his friends to pose. Among the largest of these is the Portrait of Sebastià Junyer i Vidal (Fig. 5), painted in Barcelona in 1903. While this work may record a scene the artist observed, it is also clearly a response to Degas’ earlier In a Café (L’Absinthe) (Fig. 6). Not only do both works feature a male friend of the artist — in Degas’s case it is Marcellin Desboutin, an artist and writer just as Junyer was — but both are accompanied by women of implicitly questionable morals. Degas’ sitter, the actress Ellen Andrée, poses in front of a glass of absinthe with a slumped posture and unfocused gaze, while the unidentified sitter in Picasso’s canvas wears a low-cut dress and a red flower in her hair that may mark her as a prostitute. Moreover, Degas’ painting was widely known in Paris by the time Picasso began visiting; it was called one of his most well-known paintings by one critic and was reproduced in a major article on his work in 1894. In his canvas Picasso seems deliberately to have reworked a subject identified with Degas and made it his own. The Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (Fig. 7) was the largest sculpture Degas ever made. When he exhibited the original wax version in 1881, complete with a gauze tutu and real hair tied with a silk ribbon, it provoked both high praise and harsh criticism. It remained in Degas’ studio for the rest of his life (an edition of bronzes was cast posthumously) where numerous visitors, including some who also knew Picasso, surely saw it. Thanks to these observers, as well as to the circulation of several preparatory drawings and their publication in art journals, the renown of the work was widespread even when it was not on public view. When Picasso was at work on the many sketches and preparatory works for his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907; Museum of Modern Art, New York), he seems to have drawn inspiration from Degas’ famous sculpture. Standing Nude (Fig. 8) belongs to a group of works related to the Demoiselles, although the figure did not reappear in the final painting. The canvas, however, is almost exactly the same height as the Little Dancer, and the figure’s pose, with her hands behind her back and her right leg forward, is equally close to that of the sculpture. Moreover, the radical nature of Degas’ realism also finds an echo in Picasso’s striking formal experimentation, and the “depravity” that more than one critic saw in the older work parallels the implied morality of Picasso’s figures in the Demoiselles, who were prostitutes in a brothel. In 1917, having agreed to work with Serge Diaghilev on a project for the Ballets Russes, Picasso met Olga Khokhlova, a dancer trained in Saint Petersburg who had joined the Ballets Russes six years earlier. For roughly the next decade, dance subjects became a major theme for the artist. Initially Olga appeared in many of these images, but her professional career ended after the birth of the couple’s son in 1921, so in the spring of 1925, when the family joined Diaghilev in Monte Carlo, Picasso concentrated on other members of the troupe, mostly off stage. Inevitably, he had to contend with the precedent set by Degas, whose extensive dance pictures had come more fully to light at the collection sales after his death in 1917. Two Seated Dancers (Fig. 9) combines the linear simplicity of many of Picasso’s drawings of the period with the flattened forms and multiple viewpoints of Cubism, but his dancers, if slightly more elegant, hold the same sorts of postures as the two right foreground figures in Degas’ Dancers in the Classroom (Fig. 10). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 10: Edgar Degas, (1834–1917), Dancers in the Classroom, ca. 1880 Oil on canvas, 15-1/2 x 34-13?16 inches Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Photography by Michael Agee |

|

|

In a series of monotypes usually dated to 1876–1877, Degas explicitly depicted prostitutes in a brothel as they interacted with or simply waited for clients, socialized, or washed themselves. A few of these images belonged to collectors during the artist’s lifetime, but the full extent of the group was revealed only during the sales of Degas’ collection after his death in 1917. Picasso undoubtedly knew of these works by that time if not earlier, and in 1958, as his own art collection was growing, he acquired nine of the brothel monotypes. Thirteen years later, he used these works as the inspiration for his etchings depicting brothels, and included Degas himself in the scenes. In Degas’ monotype Resting on the Bed (Fig. 11), it is unclear whether the client has left or is out of view as he approaches the woman on the bed. In Picasso’s etching (Fig. 12), the woman is similarly posed, and looks expectantly toward a male figure who is now explicitly present. The figure is Degas, a literal, if reluctant, participant, dressed in a vest and cravat, hands nervously linked behind his back. With these etchings, made not long before his death in 1973, Picasso confirmed his lifelong fascination with the work and the personality of Edgar Degas. Picasso Looks at Degas, organized by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, and the Museu Picasso, Barcelona, will be on view June 13 through September 12, 2010; The Clark is the exclusive North American venue for the exhibition. The exhibition is supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities, and with the special cooperation of Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. For information, visit www.clarkart.edu or call (413) 458-2303. |

|

|

|

|

| Sarah Lees is associate curator of European art at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. |

|

|