|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Jessica Skwire Routhier

|

|

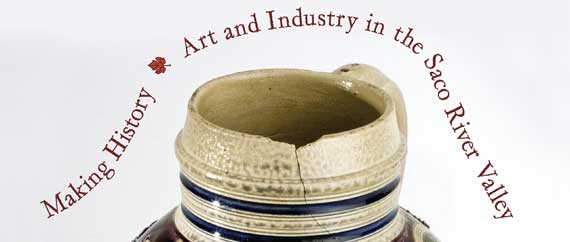

ABOVE: Fig. 1: The “Scamman Jug,” Westerwald, Germany, ca. 1689–1702. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9-3/8 in. Saco Museum; gift of Katharine Deering. Photography courtesy Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Porringer, William Simpkins (1704–1780, Boston), ca. 1762–1780. Silver. H. 2-1/8, L. 7-7/8, W. 5-3?16 in. Saco Museum

|

The Saco River makes its way from its source in New Hampshire’s White Mountains to Maine’s Atlantic coast. Its dramatic course through the Saco River Valley defines a region where people have worked for centuries to make a livelihood for themselves in concert, and sometimes in conflict, with the area’s unique geography. Even the word “Saco” (pronounced SAH-co) was made over time. The native Wabanaki referred to the river and area as “Shawakotoc,” which became “Chouacoit” in Samuel de Champlain’s Voyages of 1613 and ultimately, by 1805, the modern “Saco.”

Differences between natives and Europeans began in 1636 with the settlement in Winter Harbor, located at present-day Biddeford Pool. The outbreak of King Philip’s War in 1675 heralded the beginning of years of violent conflict. The “Scamman Jug” (Fig. 1) is a relic from this era. Family legend holds that the jug was left on a table in the Scamman home when the family was taken hostage by native tribes in 1697 and was still in situ a year later when the family returned.

|

|

|

|

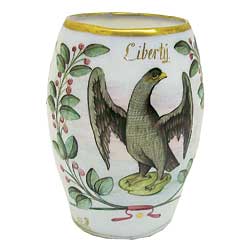

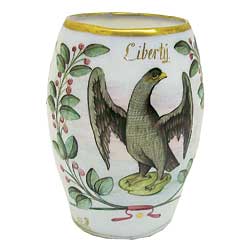

Fig. 3: Cann, probably Bohemia, ca. 1785–1820. Opaque white glass, blown, enameled, and gilt. H. 5-1/2, Diam. 3-1/4 in. Saco Museum; bequest of Almira Locke McArthur

|

From the 1600s on, the towns near the mouth of the river played an increasingly important role as shipping ports. The trees that lined the upper Saco provided raw materials both for shipbuilding and for mercantile pursuits. Lumber was shipped to Europe where building materials were scarce; it might then be traded for ceramics, glass, textiles, and other goods not readily available in New England. New wealth also brought goods from other coastal communities. By the end of the eighteenth century, luxury items as varied as an engraved silver porringer by William Simpkins of Boston (Fig. 2) and a glass cann with a patriotic American design from Bohemia (Fig. 3) had found their way into Saco River Valley homes.

One of the most significant local homes was the mansion built by Colonel Thomas (1736–1821) and Elizabeth Cutts (1744/45–1803) in 1782 on what was then called Cutts Island on the Saco River. Its prominent position overlooking the falls announced it as the finest private home in the area, and Colonel Cutts furnished it accordingly. Notably, among the imported glass, china, silver, textiles, and furniture were several pieces made not by Boston or Philadelphia masters, but by local cabinetmakers. Local artisans David Buckminster and Joshua Cumston, Abraham Forsskol, and Edward S. Moulton (Fig. 4) were all employed by this “first family” of Saco. Research done by Saco Museum staff in the 1990s has shed new light on the work of these Federal craftsmen who collaborated variously with each other on elegant veneered furniture for much of the first half of the nineteenth century.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

FAR LEFT: Fig. 4: Tall case clock, works by Edward S. Moulton (1778–1855, Saco) and case by Abraham Forsskol (1790–1864, Saco), ca. 1810–1820. Painted metal clock face with mahogany case. H. 100, W. 19-1/2, D. 9-1/2 in. Saco Museum; gift of Charles Dodge Photography by Jon Brandon, East Point Conservation Studio

CENTER and FAR RIGHT: Figs. 5, 6: John Brewster Jr. (1766–1854) Colonel Thomas Cutts and Elizabeth Scammon Cutts, ca. 1796–1801. Oil on canvas, each 74 x 30 inches. Saco Museum; gift of George Addison Emery. Photography by Ellen McDermott

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Charles Henry Granger (1812–1893), York Factories, Saco, 1830 Engraving on paper, 14 x 19 inches Published by Pendleton’s Lithography Boston. Saco Museum

|

Between 1796 and 1801, the Cuttses also invested in monumental portraits of themselves (Figs. 5, 6), beginning a long association with itinerant portrait painter John Brewster Jr., a Connecticut native who worked extensively along the Saco River Valley. Born deaf and primarily self-taught, Brewster formed connections with Maine clients through his brother Royal, a respected physician in the Saco River town of Buxton. The scope of Brewster’s career was remarkable considering the difficulties he faced in a time when education for the hearing impaired was nonexistent. Brewster ultimately painted many portraits of the Cutts children and grandchildren.2

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Carved Eagle, attributed to Joseph Romuald Bernier, known as “Bernier the Lumberman” (1873–1952, Biddeford, Maine), ca 1930s–1940s. Carved and painted wood H. 7-1/2, W. 11, D. 1/2 in. Saco Museum purchase Photography courtesy Gould Auctions

|

Four years after the death of Colonel Thomas Cutts in 1821, Cutts Island was purchased by entrepreneurs who sought to exploit the site’s capacity for large-scale industry. During the next two decades, four companies harnessed the water power of the falls making the area a center for mass textile production.3 An engraving by local artist Charles Henry Granger (Fig. 7) shows the early York Manufacturing Company’s building, newly situated in that advantageous site, with the Cutts mansion, dismantled in 1936, visible on the far right of the print.

New industry demanded a new workforce. Mill agents first recruited Yankee farmers’ daughters to card raw cotton, refill bobbins, and maintain the power looms. As the “factory girls” moved on to marriage, higher education, or business ownership, whole families emigrated to take their places at the looms. Although Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and others were among these throngs, French-speaking Canadians were by far the largest group. With the Grand Trunk Railroad providing easy access from Québec to southern Maine, and with the promise of steady work in the mills, “Francos” came by the thousands between 1845 and the mid-twentieth century, bringing their language, Catholic religion, and artistic traditions with them.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 9: Charles Henry Granger (1812–1893), Reading Room Discussion on Anti-Slavery, ca. 1840–1845. Oil on canvas, 20-3/4 x 21¾ inches. Saco Museum

|

The centuries-old Franco wood-carving tradition was carried on locally by artisans such as Saco’s Adelard Coté (1899–1974) and, Biddeford’s Romuald Bernier (1873–1952) also known as “Bernier the Lumberman,” whose whimsical carvings (Fig. 8) have appeared in major auction catalogues since the 1980s. Bernier’s identity, however, had remained mostly a mystery; Robert Bishop’s American Folk Sculpture (1974), for instance, identified him only as “Bernier.” No life dates were provided and he was thought to be active around 1900 to 1910. After purchasing three of his carvings at auction in 2008 and 2009, the Saco Museum began research into his life, and with help from descendants still in the area, pieced together the story of this Canadian native who immigrated to Biddeford in the 1890s, lost the use of both legs in a lumbering accident in the 1920s, and had turned to wood carving as a new profession by the 1930s.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10: William S. Gookin (1799–1872), Saco Falls, 1829. Oil on canvas, 24-7?16 x 30-1/8 inches. Saco Museum; gift of Mrs. Thomas Decatur, Boston

|

The arts have flourished in many forms in the Saco River Valley. Founding members of the York Institute (now the Saco Museum), established in 1866, included artist Charles Henry Granger and inventor/entrepreneur John Johnson, both of whom had already made significant contributions to science, society, and the visual arts. Johnson, a Saco native, was an important figure in early photography, designing a series of sophisticated daguerreotype cameras with his partner Alexander Wolcott. Granger, also born in Saco, was a skillful portrayer of local scenes and personages, and active in environmental conservation, historic preservation, and abolitionism. His Reading Room Discussion on Anti-Slavery (Fig. 9) depicts several identifiable Saco individuals (including himself, seated at lower left) debating that divisive issue under the silent observation of the allegorical figures on the left side of the canvas.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11: William Russell Smith (b. Scotland, 1812–1896), Sawyer’s Mountain from the Saco, ca. 1850. Oil on paper, 7 x 9 inches Saco Museum purchase

|

By the second half of the nineteenth century, factory life and the logging industry dominated the lower half of the river, and many Saco citizens shared America’s general anxiety that the wilderness was being taken over by industry and urbanization. Landscape painting became the fashion among artists and patrons of the area. Local artists such as landscape painter Gibeon Bradbury painted scenes that strove to capture the purity of the southern Maine landscape, while William S. Gookin celebrated the blending of nature and industry in Saco Falls (Fig. 10).

Visiting landscape painters also played a large role in the development of the area as a tourist destination. Nationally recognized artists like Russell Smith (Fig.11) and Albert Bierstadt (Fig. 12) brought their Saco River views back to galleries and patrons in major northeast cities, helping to promote the upper Saco River Valley as a beautiful and restful retreat. The coast also became a center for tourism, with Saco Bay’s miles of white sand beaches and the various entertainments of Old Orchard Beach providing a range of attractions. From its source in Crawford Notch to its Atlantic coastline, the Saco River corridor became one of the most painted and most visited areas in the entire United States.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12: Albert Bierstadt (b. Germany, 1830–1902), White Mountains, New Hampshire, ca. 1860. Oil on canvas, 7 x 9 inches Saco Museum; bequest of Mary Merrill

|

The works of art and decorative objects that were created in the Saco River Valley are the subject of Making History: Art and Industry in the Saco River Valley, a new, permanent exhibition at the Saco Museum, Saco, Maine, which explores the ways in which these works and the ideas behind them have intersected over a period of more four hundred years. Making History opens May 29, 2010, with satellite exhibitions at the Dyer Library and the Saco Transportation Center. An illustrated handbook, with contributions by Jessica Skwire Routhier, Camille Smalley, Marie O’Brien, and Darren French will be available in the Saco Museum shop, Saco, Maine. For more information, call (207) 283-3861 or visit www.sacomuseum.org.

|

|

|

Jessica Skwire Routhier is director of the Saco Museum, Saco, Maine, and co-author of Saco Revisited, published in 2010 by Arcadia Publishing as part of their Images of America series.

|

|

|

1. Thomas Hardiman, “Veneered Furniture of Cumston and Buckminster, Saco, Maine,” Antiques (May 2001): 753–761. His research is ongoing.

2. Thirteen Cutts family portraits are in the Saco Museum’s collection.

3. Textile factories included York Manufacturing Company (incorporated 1830), Saco Water Power Company (1837), Laconia Manufacturing Company (1841), and Pepperell Manufacturing Company (1850).

|

|

|

|

|

|