|

Displaying items by tag: Edward Hopper

After twenty-two years, Nicholas Capasso will be leaving his post at the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, MA. Capasso, who is currently the deCordova’s deputy director for Curatorial Affairs, has been named the new director of the Fitchburg Art Museum and will start his latest venture on December 3.

During his time at the deCordova, Capasso has overseen a permanent collection that included 3,500 objects, changing gallery exhibitions, and an outdoor sculpture park. He helped to bring recognition to the institution and to reposition it as an important contemporary museum.

While Capasso specializes in contemporary art, he is eager to work with the Fitchburg Art Museum’s collection that spans more than 5,000 years and includes American and European paintings, prints, drawings, ceramics, decorative arts, and Greek, Roman, Asian, and pre-Columbian antiquities. The Museum’s collection, which is housed between twelve galleries, includes works by William Zorach, John Singleton Copley, Joseph Stella, Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, Charles Sheeler, Walker Evans, and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Capasso will take over the role of director from the soon-to-be-retired Peter Timms who has held the position since 1973.

The Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.’s oldest art museum, has been losing money for years and is currently in need of at least $130 million in renovations. The only major museum on the Mall that is privately owned, times have been tough for the Corcoran who must charge admission and raise large amounts of money to survive. Attendance has dropped drastically and donations to the museum have roughly halved since the recession.

The Corcoran’s commanding Beaux Arts façade and top-notch collection of 17,000 works including pieces by Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet, and Willem de Kooning are simply not a big enough draw to keep the institution afloat, especially when every other institution on the Mall offers free admission. The Corcoran’s board of trustees are currently debating between a number of options to keep the museum active including selling the current building, combining forces with another institution, and moving out of the city.

While many find the loss of the Corcoran will leave the Washington Mall with a gaping hole, the museum announced that they have been discussing possible solutions with the National Gallery of Art, George Washington University, and a few other unnamed institutions. The Corcoran hired a real estate firm as its adviser in September and hopes to have its future mapped out by the first half of 2013.

The District of Columbia Historic Preservation League is looking to extend the landmark designation for the Corcoran’s exterior and interior. If the institution were approved, any major construction would be subject to public review.

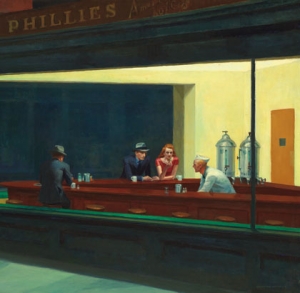

Best known for his paintings of stark diner scenes, snapshots of city life, and quiet portraits of the American landscape, there is much more to Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) oeuvre than one might think. Referred to as a romantic, a realist, a symbolist, and even a formalist, the exhibition, Paintings by Edward Hopper (1882–1967) currently on view at the Grand Palais, Galeries Nationales in Paris aims to explore each facet of Hopper’s artistic identity.

Divided chronologically into two main parts, the first section of the exhibition covers Hopper’s early work from 1900 to 1924. During this time Hopper studied at the New York School of Art under Robert Henri, the founder of the Ashcan School of realism. Hopper also spent nearly a year in Paris in 1906, followed by shorter stays in 1909 and 1910.

The first part of the exhibition sets out to compare Hopper’s early work to that of his contemporaries as well as to the art he saw while in Paris. While in Europe, Hopper was influenced by such things as Degas’ original angles to Vermeer’s use of light. He was also moved by the soft, harmonious nature of Impressionism, which is reflected in his work from the time. This work is in sharp contrast to the almost gritty realism Hopper favored back in the United States.

1924 marked a turning point in Hopper’s career. After successful exhibitions of his watercolors of neo-Victorian houses in Gloucester, Massachusetts at the Brooklyn Museum and the Franck Rehn’s Gallery (New York), Hopper enjoyed commercial success and was able to fully devote his life to his art. Hopper’s watercolors mark the second section of the Grand Palais exhibition and feature the iconic paintings most people associate with the artist.

Curated by Didier Ottinger, assistant director of the MNAM – Center Pompidou, the exhibition of Hopper’s work will be on view through January 28, 2013.

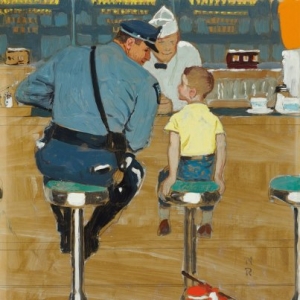

Held in New York on September 25th, Christie’s American Art sale counted two Norman Rockwell works on paper as the top lots. Study for ‘The Runaway,’ perhaps the artist’s most iconic image, brought in $206,500. The original estimate for Study at auction was $80,000–$120,000. In 1958, the completed work, which features a young boy at a diner in conversation with a policeman, was used as a Saturday Evening Post cover.

The other Rockwell that fared well was Keeping His Course (Exeter Grill) which had an estimate of $100,000 to $150,000 and ended up selling for $218,500. The work was originally conceived as an illustration for the book Keeping His Course (1918) by Ralph Henry Barbour. A less recognizable Rockwell, A Man’s Wife, didn’t quite reach it’s $30,000–$50,000 estimate and ending up selling for $27,500.

Edgar Alwin Payne’s Western painting La Marque Lake, High Sierra more than doubled its $25,000–$35,000 estimate when it sold for $80,500. Other works that exceeded expectations were Andrew Wyeth’s watercolor, Front Door at Teel’s (estimate: $50,000–$70,000), that realized $93,700 and Josef Mario Korbel’s Andante (Dancing Girls) (estimate: $30,000–$50,000), a bronze that brought in $62,500.

The auction offered over 160 lots including Impressionist and Modernist works, Western pieces, illustrations, and bronzes. Artists on the block included Stuart Davis, Milton Avery, Will Barnet, Edward Hopper, and William Merritt Chase. Expected to reach in excess of $2.5 million, the total sale realized for the auction was $2,649,475.

While the auction reached its estimate, only 63% sold by lot and 76% by value. Debra Force of Debra Force Fine Art, Inc. said, “63% is terrible but there are many reasons for the poor performance. September is too early in the season for a sale. People are just getting back from summer, putting kids in school, and it’s in the middle of the Jewish holidays.” Force added, “The important collectors don’t look at these mid-season sales. They should, but they’re waiting for the major sale.“

Gavin Spanierman of Gavin Spanierman Ltd. echoed Force’s sentiments. “63% is pretty scary if you’re a seller but that’s representative of mid-season sales. However, the fact that the two Rockwells did well considering they were not phenomenal, shows that there is strength in the market.”

It's one of the ultimate images of summer: a woman in a short, pink slip sits on a bed, her knees pulled up to her chest, gazing out a window. Her hair is tucked back into a bun. Her bare arms rest lightly on her bare legs.

Edward Hopper painted her in 1952 for a work called Morning Sun. The picture has been widely reproduced for decades. But on a recent visit to its home at the Columbus Museum of Art in Columbus, Ohio, it was nowhere to be found.

"It's on loan right now to an exhibition," explains Melissa Wolfe, the museum's curator of American art. "It travels a lot. It's a very well-requested painting."

Many of Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) most admired paintings are night scenes. An enthusiast of both movies and the theater, he adapted the device of highlighting a scene against a dark background, providing the viewer with a sense of sitting in a darkened theater waiting for the drama to unfold. By staging his pictures in darkness, Hopper was able to illuminate the most important features while obscuring extraneous detail. The settings in Night Windows, Room in New York, Nighthawks, and other night compositions enhance the emotional content of the works—adding poignancy and suggestions of danger or uneasiness.

Edward Hopper makes us all voyeurs. His best-known works allow us to watch people so absorbed that they are not only indifferent to what goes on around them, but also completely unaware of our presence. Sometimes our viewpoint is indeterminate. At other times, we are outside in the dark, peering unobserved into nondescript hotel rooms and lobbies, middle-class apartments and middle-management offices, automats and late-night bars. Everything has the illicit appeal of a lighted room glimpsed as we pass by on a bus.

Perhaps because of this overtone of the forbidden, Hopper also turns us into storytellers. The insignificant, quintessentially American moments that he allows us to see become imminent dramas, full of meaning. The potency of his pictures ultimately depends on firm structure and the play of light—when the implicit narrative seems more important than the formal elements, the pictures shift uncomfortably toward illustration—but it's hard to resist speculating upon what led up to the ambiguous situation before us and what the outcome might be. As his preparatory drawings reveal, Hopper often conflated many accumulated observations into a single image, but his paintings can seem so specific about time, place, social stratum and more, that they can approach the stop-time realm of photography or the fictive reality of cinema.

That evocative specificity is why movie directors, including Alfred Hitchcock, have looked to Hopper for inspiration. It's also what generated the one-act opera "Later the Same Evening," with music by John Musto and libretto by Mark Campbell, performed at this season's Glimmerglass Festival. In it, the dispassionately rendered personages from five of Hopper's most celebrated urban interiors—"Room in New York," "Hotel Window," "Hotel Room," "Two on the Aisle" and "Automat"—become named characters; reproductions of the paintings hang in a neat row across the set. We learn the characters' back stories and receive hints of their futures. They come together at a performance of a musical, a conceit suggested by "Two on the Aisle," which depicts an almost empty theater as the first audience members arrive. Then everyone separates, except for the young woman from "Automat" and an interpolated young man.

Edward Hopper -- the American artist of such classic paintings as "Nighthawks" and "Early Sunday Morning" -- is about to receive an honor from the U.S. Postal Service. On Aug. 24, a new postage stamp based on his circa-1935 painting "The Long Leg" will be unveiled at a public ceremony at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, where the original artwork resides.

The new "forever" stamp is the latest in the Postal Service's American Treasures stamp series, which also includes homages to Winslow Homer, Mary Cassatt and John James Audubon. The stamp features a cropped image of Hopper's original painting.

The Postal Service had originally planned to release the Hopper stamp in 2009 but delayed in doing so because of the recession.

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art presents Edward Hopper ‘Maine’ an exhibition on view from July 15 through Oct 16, 2011.

Organized in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, Edward Hopper’s Maine brings together 88 of these early paintings, watercolors, drawings, and prints. With loans from nearly thirty public and private collections, this exhibition represents the first comprehensive examination of this crucial period of artistic experimentation. Among the institutions who have generously loaned works are the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

After studying painting with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, Edward Hopper traveled to Europe three times between 1906 and 1910. Once he settled in his New York studio, he began to reconcile his indigenous training with the painterly traditions that he had encountered abroad, attempting to set himself apart from legions of other downtown artists. Like many painters, he sought refuge from New York City summers in coastal colonies, initially in Gloucester, MA, then traveling to Maine for the first time in 1914. Hopper spent two consecutive summers in Ogunquit, the second of which saw his plein-air painting thwarted by fog. In 1916 he decamped for the more remote Monhegan Island, where he would return for the next three summers, one of a very diminished number of wartime visitors.

At the core of Edward Hopper’s Maine are nearly all of the thirty-two oil sketches that the artist executed during the summers he spent on Monhegan. These small panels, many of which were never shown in the artist’s lifetime and continue to be under-exhibited, are astonishing in their jewel-like hues, painterly execution, and spatial ambiguity. Seen en masse, these oils yield unique insight into the artist’s process by revealing his sustained contemplation of similar motifs. Stalking his subject, Hopper painted the Monhegan headlands repeatedly, but under such varying conditions, and from such different vantages, that the works’ seriality is not immediately apparent.

By 1924, Edward Hopper had taken up watercolor painting and begun to exhibit at the Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery in New York, where he would enjoy his first significant commercial success. Returning to Maine in 1926 (this time to Rockland), and again in 1927 and 1929, he painted some of his most iconic Maine images — lighthouses, beam trawlers, dories, and coastal villages like Cape Elizabeth. Natural beauty becomes increasingly peripheral to Hopper’s study of structures and vessels, and one begins to perceive here the heightened tension between rational operations and subjective sensations (“the most exact transcription of my most intimate expressions”) that will characterize his mature painting. This concentrated look at a significant body of rarely seen work sheds new light on one of the greatest painters of the twentieth century.

A 176 page, fully illustrated catalogue accompanies Edward Hopper’s Maine published by DelMonico Books-Prestel. Contributors include Hopper scholar Carol Troyen, actor-collector-writer Steve Martin, poet Vincent Katz, Whitney Museum curator Carter Foster, Kevin Salatino and Diana Tuite.

www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum

The essentials of childhood form us all. Even when we rebel against them, our thoughts, beliefs, dreams, and preferences are consequences of our birthplace and earliest years, and Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was no exception. His artistic personality was shaped by his roots in Nyack, New York, and the town and its environs helped contribute to the figure he would become. Nyack’s general history, topography, and architecture were critical to his early preoccupations and his later pursuits, and the particulars of his family’s own house at 82 North Broadway afforded him an ideal place to flourish. During the period he lived in Nyack, which lasted until 1910, when he rented his first known studio in Manhattan, Hopper began formulating the central themes of his art, those which distinguished him from everyone else, and were his and his alone.

|

|

|

|

|