|

Displaying items by tag: Willem De Kooning

While hedge-fund owner, Steven A. Cohen, is embroiled in a financial fiasco, the art world is anxiously waiting to see what will become of his impressive art collection. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has informed Cohen that his $14 billion company, SAC Capital Advisors LP, could be at the center of an insider-trading lawsuit. The SEC is currently suing SAC Capital’s former portfolio manager, Mathew Martoma.

Cohen, who is worth $9.5 billion, started building his collection around 2001 and is now regarded as one of the biggest and most influential art collectors. Once a major buyer of Impressionist works, Cohen began collecting more contemporary pieces and helped raise prices of big-name artists like Damien Hirst, whose shark in formaldehyde, titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, he bought for $8 million.

Cohen’s collection also includes works by Vincent van Gogh, Edouard Manet, Willem de Kooning, Pablo Picasso, Paul Cezanne, Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, and Jasper Johns. If Cohen’s troubles worsen, he may be forced to dismantle his carefully assembled collection and begin selling his artworks.

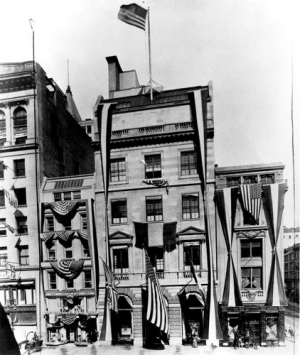

The Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.’s oldest art museum, has been losing money for years and is currently in need of at least $130 million in renovations. The only major museum on the Mall that is privately owned, times have been tough for the Corcoran who must charge admission and raise large amounts of money to survive. Attendance has dropped drastically and donations to the museum have roughly halved since the recession.

The Corcoran’s commanding Beaux Arts façade and top-notch collection of 17,000 works including pieces by Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet, and Willem de Kooning are simply not a big enough draw to keep the institution afloat, especially when every other institution on the Mall offers free admission. The Corcoran’s board of trustees are currently debating between a number of options to keep the museum active including selling the current building, combining forces with another institution, and moving out of the city.

While many find the loss of the Corcoran will leave the Washington Mall with a gaping hole, the museum announced that they have been discussing possible solutions with the National Gallery of Art, George Washington University, and a few other unnamed institutions. The Corcoran hired a real estate firm as its adviser in September and hopes to have its future mapped out by the first half of 2013.

The District of Columbia Historic Preservation League is looking to extend the landmark designation for the Corcoran’s exterior and interior. If the institution were approved, any major construction would be subject to public review.

165 years ago, the Knoedler Gallery opened its doors in New York and went on to help create some of the country’s most celebrated collections including those of Paul Mellon, Henry Clay Frick, and Robert Sterling Clark. Throughout the years, top-notch works by artists such as van Gogh, Manet, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, Louise Bourgeois, and Willem de Kooning passed through the gallery. When the Soviet government sold hundreds of paintings from the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad in the 1930s, they chose to work with Knoedler to sell paintings by masters like Rembrandt, Raphael, and Velazquez.

Knoedler’s exemplary past is often forgotten as the gallery’s present has been mired in lawsuits and accusations that the company’s former president, Ann Freedman, was in the business of selling fakes. Last year, Knoedler Gallery closed its doors for good.

This week, Los Angeles’ Getty Research Institute announced that it had bought the Knoedler Gallery archive. Spanning from around 1850 to 1971, the archive includes stock books, sales books, a photo archive and files of correspondence, including letters from artists and collectors, some with illustrations. The Getty was interested in Knoedler’s archive because it offers an expansive glimpse into the history of collecting and the art market in the United States and Europe from the mid-19th century to modern times.

The archive was purchased from Knoedler’s owner, Michael Hammer, for an undisclosed amount. Meticulously preserved, the archive will be available to scholars and digitized for online research after the Getty catalogues and conserves it all.

Domenico De Sole, chairman of the fashion powerhouse, Tom Ford International, is suing Michael Hammer, chairman of the disgraced Knoedler Gallery. De Sole and his wife, Eleanore, claim that Hammer sold the couple a fake Mark Rothko (1903–1970) painting (Untitled, 1956) for $8.3 million back in 2004. The allegation against Hammer is an amendment to a lawsuit that was originally filed against Knoedler on March 28.

De Sole’s suit is one of three against Knoedler and its former director, Ann Freedman. The suits all claim that Knoedler Gallery knowingly sold counterfeits. Between the three cases, the plaintiffs are seeking more than $70 million in damages.

Knoedler closed on November 30, 2011 after 165 years in the art world. A claim that the gallery sold a fake Jackson Pollack (1912–1956) painting for $17 million was the reason for Knoedler’s abrupt departure.

In addition to Hammer, the De Sole suit has introduced three new defendants to the ongoing Rothko/Knoedler case. Glafira Rosales, a Long Island art dealer who consigned artworks to Knoedler is newly involved as is as Jaime Andrade, a former Knoedler employee who introduced Rosales to the gallery. Jose Carlos Bergantinos Diaz, Rosales companion and business partner has also been added to the suit.

When Knoedler sold Untitled, 1956 to the De Soles, Freedman claimed that a Swiss collector had bought it directly from Rothko, and after the collector’s death, Knoedler was responsible for selling the work on his son’s behalf. The gallery had bought the painting from Rosales a year earlier for $950,000 and relied on her work about the painting’s provenance. Suspicions arose after Knoedler Gallery closed amidst the Pollack scandal and the De Soles’ lawyers hire a forensic conservator who found the painting’s marks and composition were inconsistent with Rothko’s technique.

The now-shuttered Knoedler & Co. gallery, which is the subject of several lawsuits charging it sold fakes, will sell nearly three dozen works from its remaining inventory at auction this fall.

Thirty-four pieces of art from the gallery’s inventory that include works by Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, Milton Avery, and Walker Evans, are scheduled to be auctioned off by Doyle New York on Nov. 13, said Harold Porcher, vice-president and director of modern contemporary art at Doyle.

Federal District Court Judge Paul G. Gardephe’s résumé includes many impressive accomplishments but not an art history degree. Nonetheless he has been asked to answer a question on which even pre-eminent art experts cannot agree: Are three reputed masterworks of Modernism genuine or fake.

Judge Gardephe’s situation is not unique. Although there are no statistics on whether such cases are increasing, lawyers agree that as art prices rise, so does the temptation to turn to the courts to settle disputes over authenticity. One result is that judges and juries with no background in art can frequently be asked to arbitrate among experts who have devoted their lives to parsing a brush stroke.

The three cases on Judge Gardephe’s docket in Manhattan were brought by patrons of the now-defunct Knoedler & Company who charge that the Upper East Side gallery and its former president Ann Freedman duped them into spending millions of dollars on forgeries.

The judge’s rulings may ultimately rely more on the intricacies of contract law than on determinations of authenticity. But the defendants and plaintiffs are busily assembling impressive rosters of artistic and forensic experts who hope to convince the judge that the works — purportedly by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko — are clearly originals or obvious fakes.

Of course judges and juries routinely decide between competing experts. As Ronald D. Spencer, an art law specialist, put it, “A judge will rule on medical malpractice even if he doesn’t know how to take out a gallstone.” When it comes to questions of authenticity, however, lawyers note that the courts and the art world weigh evidence differently.

Judges and juries have been thrust into the role of courtroom connoisseur. Legal experts say that, in general, litigants seek a ruling from the bench when the arguments primarily concern matters of law; juries are more apt to be requested when facts are in dispute.

The first thing visitors will see at the entrance to the Museum of Modern Art’s sprawling Willem de Kooning retrospective, which opens on Sunday, is a wall of photographs that chronicle six stages in the creation of the legendary painting “Woman I” (1950-52). John Elderfield, MoMA’s chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture, said he chose these images as a starting point because they illustrate “that de Kooning was an artist about process.”

For the last six years Mr. Elderfield has immersed himself in the work of de Kooning, who helped define the shape of postwar American art. The artist, who died in 1997, was especially known for his large and luscious canvases of riotous brush strokes and curving forms, and for his preoccupation with the female figure, a subject he returned to in different guises throughout his career.

Mr. Elderfield has a big story to tell. The exhibition includes some 200 works made over nearly seven decades — paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures — and occupies the museum’s entire 17,000-square-foot sixth floor, a first for an exhibition since MoMA reopened after its expansion in 2004.

It is also the first comprehensive look at de Kooning’s work in nearly 30 years (The Whitney Museum of American Art held the last thorough retrospective in 1983.)

“This is an artist people want to know of,” Mr. Elderfield said, adding that he believed de Kooning would be “rediscovered by a new generation.”

Because the price of postwar art has escalated so drastically over the last few years, with major works by de Kooning fetching astronomical prices, the show, which consists primarily of loans, is costing MoMA greatly. While the museum will not give an exact figure, experts familiar with the retrospective say it includes more than $4 billion worth of art: an enormously costly group of works to transport and insure, making it perhaps the most expensive exhibition in the institution’s history.

Delving into the career of a master like de Kooning would seem unlikely to yield discoveries, given that his story has been told so many times, including in a biography that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2005: his arrival in New York from his native Netherlands as a stowaway in 1926; his hard-drinking life in cold-water lofts; his first one-man show at 44; and his eventual fame as the artist who epitomized the improvisational bravura of Abstract Expressionism. (De Kooning’s waning years are well known too: in the 1980s he was given a diagnosis of dementia, and in 1989 he was declared incompetent by his lawyer and his daughter, Lisa.)

But Mr. Elderfield approached his subject as if on an art historical treasure hunt. As he started working on the exhibition, one clue led to another and another, until he was able to piece together new insights from technical studies, photographs, popular postwar films and even magazine clips about movie stars of the day.

WILLEM DE KOONING

THE FIGURE: MOVEMENT AND GESTURE

Paintings, Sculptures, and Drawings

On view at the Pace Gallery, NY from April 29 to July 29, 2011

The Pace Gallery is honored to present Willem de Kooning: The Figure: Movement and Gesture, on view at 32 East 57th Street from April 29 through July 29, 2011. This will be the first exhibition at Pace devoted to the artist since the gallery announced exclusive representation of the estate last fall. Willem de Kooning: The Figure: Movement and Gesture features nearly forty paintings, drawings, and sculptures from the late 60s through the late 70s, including a number of private loans and rarely seen paintings. A catalogue with an essay written by art historian Richard Shiff will accompany the exhibition. An opening reception will be held at the gallery on April 28 from 6 to 8 pm.

From the late 60s to the late 70s de Kooning explored the figure with new gestural liquidity, merging the figure into landscape and working in sculpture for the first time. The Figure: Movement and Gesture focuses on the movement of transformation from figuration into abstraction and the complex ways that de Kooning depicted motion as he rendered the human figure. “The figure,” de Kooning stated during this period, “is nothing unless you twist it around like a strange miracle.” The artist twisted, turned, and contorted the figure into the landscape as he investigated form, blurring the edges into abstraction and bringing it back into moments of clarity.

This new consideration of the figure coincided with de Kooning’s permanent move to the Hamptons from Manhattan in 1963 and a growing interest in a pastoral vocabulary. As de Kooning resumed painting in his new studio, the figures that emerged were decidedly different from his anatomically distorted, wild-eyed women from the 50s. In contrast to the dark lines of charcoal or black enamel that bound those earlier compositions, brushstroke and color were freed from form. As the artist experienced the motion of the figure and of his own strokes the distinction between figure and ground diminished until woman was no longer differentiated from landscape.

In Woman, 1969, a rarely seen painting, on view here for the first time in New York, de Kooning pulls the twisting figure out from fields of color. Amityville, 1971, reveals glimpses of “feet, hands, and perhaps a central torso,” Shiff writes, “But what do we actually see? The bright colors—white, yellow, red, and blue, all distributed nearly equally throughout the field of this image—create a sensory tension between the linear configurations and the chromatic contrasts. To concentrate on the one is to be distracted by the other, with the result that perceptual movement—now this, now that—is built into the painting.”

De Kooning’s process of building a painting was entwined with the movement that it depicted; insistent on working each painting from all four sides, he rotated the paintings into different orientations—a vertical composition becoming horizontal and vice-versa. As he turned the image of the figure around in his mind, considering it from every angle, “it was touch,” Shiff explains, “that guided his contact with the pictorial surface.” At times de Kooning drew with his eyes closed, with his left hand or both hands, drawing from the moving image on a television screen, feeling his own body into the position of the figures that he would paint—internalizing the motion he wished to depict. The paintings mutated constantly, rarely considered finished, and a day’s work was often scraped down to begin anew over the traces of pigment that preceded it.

De Kooning worked on multiple paintings simultaneously, using vellum to invert, mirror, or replicate a movement and transfer the image from one work to another or to study a movement from both sides, working on both recto and verso of the page. Examples of the artist’s works on vellum will also be on view, mounted so that they will be visible from both sides. Twenty drawings will provide a glimpse at the quickest, most direct expression of hand to paper. “[My] drawings are fast,” de Kooning once remarked, “like snapshots.”

The time period presented coincides with de Kooning’s first foray into sculpture in 1969, the result of a chance encounter on a visit to Rome with an old friend who owned a foundry. Working with clay enabled the artist to connect to the human body without the interruption of the brush, and he responded to the visceral act of pushing, squeezing, and shaping the form as he considered it in three dimensions. In 1971 he began sculpting again in his East Hampton studio, making works larger than those he had made abroad, often working with dexterous wire armatures that could accommodate the heavy masses of wet clay he applied. In 1972, de Kooning made several figures related to the paintings that immediately preceded his work with sculpture, such as Cross-legged Figure (1972), a bronze figure twisted around a central axis with its limbs flayed outwards. Hostess (1973), a bronze sculpture measuring 49" x 37" x 29," will also be on view.

Willem de Kooning’s relationship with Pace dates to the gallery’s origins in 1963 and spans five decades, during which the gallery has presented more than a dozen exhibitions devoted to the artist. These include three groundbreaking shows that have greatly contributed to the scholarship on de Kooning, providing new revelations and insight into his richly nuanced career. De Kooning/Dubuffet: The Women (1991) was the first full-scale exhibition to pair both artists’ series of women, painted almost simultaneously on each side of the Atlantic; De Kooning/Dubuffet: The Late Works (1993) explored affinities in the final works of the artists, and Willem de Kooning and John Chamberlain: Influence and Transformation (2001) examined two Abstract Expressionists working across generations and mediums.

At Pace, the de Kooning estate is reunited with contemporaries and friends from the artist’s life, including the estates of Adolph Gottlieb, Isamu Noguchi, Ad Reinhardt, and Mark Rothko. For decades Pace artists ranging from Chuck Close and Jim Dine to Robert Irwin have noted de Kooning’s influence and their own admiration for his work. Born on April 24, 1904 in Rotterdam, de Kooning would become recognized as a leader of the New York school by the 1950s. In 1948, Josef Albers invited de Kooning to teach at Black Mountain College, where Robert Rauschenberg and John Chamberlain, among others, studied. Moving from figuration to abstraction—and at times working simultaneously in both, de Kooning’s work underwent radical stylistic shifts from decade to decade.

This exhibition precedes a major retrospective devoted to the artist at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, which will examine the development of the artist’s career over nearly seven decades through more than 200 works from public and private collections, representing nearly every type of technique and subject matter that the artist worked in. De Kooning: A Retrospective will be on view from September 18, 2011 through January 9, 2012. Willem de Kooning’s work has been featured in hundreds of solo and group exhibitions internationally and can be found in nearly every important public collection around the world.

For more information about Willem de Kooning: The Figure: Movement and Gesture, please contact the Public Relations department of The Pace Gallery at 212.421.8987. For general inquiries, please email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.; for reproduction requests, email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

|

|

|

|

|