|

|

|

|

by Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa Minardi

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Spice box attributed to Thomas Coulson (1703–63) and possibly John Coulson (1737–1812), Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1740–1750. Walnut, white oak, red cedar, sumac, holly, brass. H. 19-3/4, W. 16-1/4, D. 11 in. Collection of Leslie Miller and Richard Worley.

|

"The subject is too new a field of research for me to do more than blaze a somewhat imperfect trail," Esther Stevens Fraser wrote in a pioneering 1925 article on painted chests, one of the first studies of southeastern Pennsylvania furniture.1 Although much work has been done since Fraser's early efforts, most scholarship has focused on Philadelphia or particular forms or ethnic groups. William Penn's policy of religious tolerance resulted in Pennsylvania being the most culturally diverse of the thirteen colonies--home to English, Irish, and Welsh Quakers; Scots-Irish Presbyterians; and German-speaking Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, Moravians, Schwenkfelders, and other sectarian groups. This diversity was reflected in the region's furniture through locally distinctive expressions of form, ornament, or construction. These localisms, together with the people who made and owned the furniture, are the focus of Winterthur's latest exhibition and publication Paint, Pattern & People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725-1850, on view from April 2, 2011, through January 8, 2012.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Desk-and-bookcase made for William Montgomery, Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1725–1740. Cherry, chestnut, tulip-poplar, oak, white pine, walnut, holly, brass. H. 76, W. 37-3/4, D. 21-1/2 in. Rocky Hill Collection.

|

Over the past four years, more than 250 private and museum collections, as well as dozens of auctions and antiques shows were visited to locate documented furniture for which a maker and/or original owner was known. This search was aided by a strong network of collectors, dealers, and museum colleagues who generously shared their time and knowledge as hundreds of pieces of furniture were examined. Ultimately distinctive groups began to emerge that helped define locally specific characteristics and some remarkable new discoveries were made.

Spice boxes are one of the most iconic furniture forms associated with southeastern Pennsylvania, especially Chester County. Although many examples have inlaid dates and owners' initials on them, few are known with documentation of a maker. When this diminutive spice box with line-and-berry inlay (Fig. 1) was discovered in a private collection, it not only had a history of ownership in the Hartshorn (Hartshorne) family of West Nottingham, Chester County, but also the partial signature of a joiner, John Coulson. Inscribed on several of the drawer bottoms is the name "John Coul...," believed to be John Coulson (1737-1812). At the time this box was made, John was likely apprenticed to his father, Thomas, a documented joiner. Thomas Coulson was born in 1703 in the village of Hartshorne, Derbyshire, England. When Thomas died in 1763 he left "to my son John Coulson all the Utensils of Husbandry on said Place and Two Horses and Two Cows and half my Joyners Tools." When John Coulson died in 1812, he may no longer have been working as a joiner as only some "old plains" and "Half Inch poplar Boards" are listed in his inventory.2 Living in the same community, and perhaps having come at the same time to Chester County from the village of Hartshorne in England, it is not surprising that there were close ties between the Coulsons and the Hartshorns. The association of this spice box with the Nottingham area helps to connect similarly inlaid and ornamented pieces without family histories or makers' signatures to that same locale.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Tall-case clock, movement by Benjamin Chandlee Jr. (1723–1791), case by Jacob Brown (1746–1802), Nottingham area, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1788. Walnut, hard pine, tulip-poplar, brass, iron, bronze, steel, glass. H. 107-1/2, W. 25-1/2, D. 14-1/2 in. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John McDowell Morris and Family.

|

Line-and-berry inlay appears on various forms, ranging from spice boxes to tall chests, and is highly sought after by collectors. When this double dome-top desk-and-bookcase (Fig. 2) surfaced last summer, it was the first example of the form with line-and-berry inlay to survive intact—an exciting discovery!3 Although some of the inlay on the drawer fronts relates to other known line-and-berry furniture, the organization of the rail-and-stile door panels and the inlay on them is unique. Made of cherry and constructed in one piece, this desk descended in the Montgomery family. The inlaid initials "W" and "M" at the top of the door panels are probably for the original owner, William Montgomery (1665/6–1742), a Scots-Irish Presbyterian who came to America about 1722 and settled in northern Delaware. His son Alexander Montgomery was likely the next owner, which accounts for the initial "A" that was later inlaid in the center of the cornice molding. Although the desk's maker is unknown, its stylish urban form provides early evidence of sophisticated cabinetmaking in southern Chester County.

In addition to line-and-berry inlay, the Nottingham area is noted for a distinctive group of furniture associated with cabinetmaker Jacob Brown. Nearly fifty years ago, Margaret Berwind Schiffer published a walnut tall clock (Fig. 3) made for Irish immigrant James McDowell (1742-1815), citing letters sent to McDowell in 1788 from Benjamin Chandlee Jr., maker of the movement, and Jacob Brown, who made the clock case.4 Tantalizing information, but the whereabouts of the clock and letters were unknown until online genealogy research discovered them still in the possession of McDowell descendants. A close reading of Brown's letter to McDowell then occasioned a rethinking of which Jacob Brown was the maker of the clock case. Ultimately, the correct Jacob Brown (1746-1802) was identified and the public vendue after his death provided evidence of an active shop with an extensive stock of lumber, numerous joiner's tools, and unfinished furniture — including three "Clock cases not finished." McDowell's clock has survived remarkably intact, retaining the original feet, rosettes, and two of the three original finials. With firm documentation to the Nottingham area, this clock case is key to identifying other cases from this area.5

A search for furniture associated with Scots-Irish settlers led to some of the oldest Presbyterian churches in the region. At the Donegal Presbyterian Church in western Lancaster County, just a few miles east of the Susquehanna River, a communion table with distinctive cup-and-baluster turned legs connected by a stretcher base was discovered (Fig. 4). The Donegal settlement was virtually on the western frontier when Scots-Irish immigrants erected a log church there in the early 1720s. This exceptional table was probably among the building's original furnishings. Due to the remoteness of the church and early date of the table, it may have been made by a member of the congregation—possibly carpenter James Murray, who died in 1747 possessed of saws and molding planes.6 Accompanying the table is a pewter communion service of two flagons and four two-handle cups made by William Eddon and a set of four fluted plates, or patens, made by Richard King, both of London.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Communion table, probably Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1720–1745. Walnut. H. 29, W. 47-1/8, D. 33-3/8 in. Two-handle cup and flagon, William Eddon (active 1690–1737), London, 1720–35. Paten, Richard King (active 1745–1798), London, 1745–75. Pewter. Donegal Presbyterian Church, Mount Joy, Pa.

|

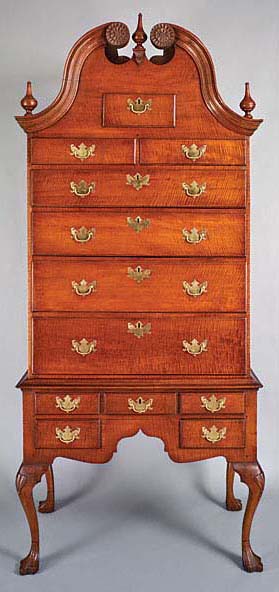

High chests with makers' signatures are rare, even from urban centers such as Philadelphia. Thus the discovery of this commanding striped maple example (Fig. 5) was remarkable as it was signed and dated by joiner Seth Pancoast in 1766. Born in Burlington County, New Jersey, to English Quakers William and Hannah (Scattergood) Pancoast, Seth presumably served his apprenticeship in Darby, Chester (now Delaware) County, where he met and married Esther Coppock in 1741. To whom he apprenticed is unknown, though James Bartram and Joseph Hibberd are likely candidates. Although the high chest has no provenance, it relates closely to a dressing table that descended in the Coppock family and possibly they were made as companion pieces. Both examples suggest that Pancoast was familiar with the work of Philadelphia artisans. The overall format of the high chest's broken-scroll pediment; central drawer in the tympanum; meticulously detailed carved rosettes; shells on the knees; and exaggerated trifid feet are distinctive and accomplished details.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Tall-case clock, movement (not original) by Edward Sanders, Pool, England, 1730–1765. Case: probably Lancaster, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1745. American black walnut (microanalysis), tulip-poplar (microanalysis), brass, iron, bronze, steel, glass. H. 91-1/4, W. 21-3/4, D. 12-1/4 in. Private collection.

|

In contrast with the chests of drawers used for storage by many English-speaking inhabitants, most Pennsylvania Germans favored the use of lift-top chests, which were usually made of either walnut, or pine or tulip-poplar if painted. Some of the more pervasive myths involve these iconic objects; the most common one is that they were "dower chests," which implies they were made exclusively for young women in preparation for marriage. In fact, both young men and women were given chests, typically in their teenage years. These chests then accompanied the owners into their married life. By and large, they were not made as dower chests. When the chest inscribed across the front "Adam Minnich in Bern Bercks gaunti im jar 1796" (Adam Minnich in Bern [Township] Berks County in the year 1796) surfaced at auction in 2006 (Fig. 6), it validated this fact in a variety of respects.7 Another myth surrounding painted chests is the assumption that the designs carry religious or symbolic meaning. Although the lions and unicorns on the Minnich chest might suggest a masculine object, the existence of an identical chest made for Maria Grim and also dated 1796 demonstrates that this decoration was equally appropriate for a female.8

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: High chest of drawers by Seth Pancoast (1718-1792), Marple Township, Chester (now Delaware) County, Pennsylvania, 1766. Maple, tulip-poplar, chestnut, maple, brass. H. 95, W. 41-5/8, D. 22-3/8 in. Winterthur Museum, promised gift of John J. Snyder Jr.

|

|

Fig. 6: Chest-over-drawers made for Adam Minnich, Bern Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1796. White pine, paint, brass, iron. H. 25-1/2, W. 50-3/4, D. 23-1/4 in. Private collection.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Liturgist’s chair attributed to Johann Friedrich Bourquin (1762–1830), Bethlehem, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1803–1806. Maple, paint, wool (modern), cotton, linen, leather, hair, iron. H. 39-1/4, W. 18-1/2, D. 18 in. Moravian Archives, Bethlehem, Pa.

|

|

Fig. 9: Urn attributed to Johann Friedrich Bourquin (1762–1830), Bethlehem, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1803–1806. Tulip-poplar, paint, gold leaf. H. 27, Diam. 16 in. Central Moravian Church, Bethlehem, Pa.

|

|

Pennsylvania German furniture dated prior to 1760 is rare and nearly all known examples lack documentation as to maker or owner. Thus the serendipitous discovery of a tall clock dated 1745 with the names of the owners, Andreas and Catharina Beierle, carved on the case was an exciting find (Fig. 7). Doubtless the work of a German émigré craftsman, the clock is ornamented with relief carving from the solid wood—a Germanic technique that would reach its zenith in Lancaster rococo furniture several decades later. Although the unusual motifs on the pendulum door were initially puzzling, research yielded an explanation. A German emigrant, Andreas Beierle (1713-1781) settled in Lancaster by 1743 and was an innkeeper and baker by trade. The motifs carved below the glass bull's-eye represent his profession: at the top is a pretzel (a traditional baker's symbol), followed by two Manchet (lemon-shape rolls) and milk bread, a special roll that is baked in pairs; both types represent the finest sort of white bread eaten at the table.9 Due to its early date, history of ownership, and close ties to European precedents, the Beierle clock provides an important link between Old and New World craft traditions.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10: John Fisher, by Lewis Miller (1796–1882), York, York County, Pennsylvania, 1808. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. H. 6, W. 3 in. York County Heritage Trust.

|

A visit to the Moravian community of Bethlehem, Northampton County, founded in 1741 led to a number of surprising finds. Among them was an oval-back liturgist's chair with fluted, square tapered legs that initially looked out of character for a Moravian church (Fig. 8). However, upon visiting the Central Moravian Church (built 1803–1806) and seeing the original pulpit, the urban sophistication of the Bethlehem community became clear. Designed in the classical style, the church was built by John Cunnius (1733-1808) of Reading, Berks County. Cabinetmaker Johann Friedrich Bourquin (1762-1830) produced much of the interior woodwork and its carved decoration. A classical urn (Fig. 9) made for atop the sounding board of the pulpit has carved ornament that bears a close relationship to that on the chair. Born in East Prussia, Bourquin was a cabinetmaker in the Moravian community of Zeist in Holland until 1791, when he moved to Silesia. In 1800 he arrived in Bethlehem and worked as a cabinetmaker for the next thirty years. Exemplifying the Moravians' awareness of the latest styles, the chair's white painted surface and upholstered oval back emulated the French taste then fashionable in Philadelphia.

John Fisher (1736–1808) of York, described in 1800 as "a German mechanic of a curious & versatile genius," was a gifted clockmaker as well as sign painter, woodcarver, and engraver.10 York chronicler Lewis Miller depicted him several times, once holding a pair of compasses (Fig. 10) evoking his occupation as a tradesman. Born in Germany, Fisher immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1749 and settled in York by 1756. Founded in 1741, York was a thriving market town by the time of the Revolution, and by 1779 more than half the taxpayers were artisans, practicing nearly forty trades.11 One of Fisher's most impressive clocks is a musical one with an eight-day movement and orrery that indicates the positions of the sun, moon, and planets (Fig. 11). The brass dial is engraved "John Fisher / York Town," along with Latin inscriptions from Virgil's Aeneid and Georgics near the central figure of Zeus and around the orrery. The clock plays seven tunes; a pinned brass cylinder adjusts automatically so that a different one plays each day of the week.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11: Tall-case clock, movement by John Fisher (1736–1808), York, York County, Penn-sylvania, 1790–1800. Walnut, tulip-poplar, brass, bronze, iron, steel, silver; glass. H. 104-3/4, W. 27, D. 15 in. York County Heritage Trust.

|

|

Fig. 13: Kitchen cupboard by Jacob Blatt (1801–1878), Bern (now Centre) Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1848. Tulip-poplar, maple, white pine, paint, brass, iron, glass. H. 82-3/4, W. 58-1/2, D. 20 in. Winterthur Museum purchase with funds drawn from the Centenary Fund and acquired through the bequest of Henry Francis du Pont (2008.28).

|

|

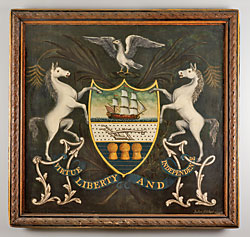

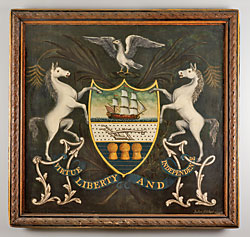

Fisher was also a talented painter and woodcarver. In 1796 the York County Commissioners paid him £25 for "Painting the Coat of Arms to and for the use of the Court House" and £5 for "Carving and Guilding the Image to the same."12 The painting survives (Fig. 12) and features two white horses flanking a central shield topped by an eagle, all above the state motto "Virtue, Liberty, and Independence." Within the shield are images symbolizing Pennsylvania's heritage, including a ship under full sail, a plow, and three sheaves of wheat. Given Fisher's skill as a carver, he probably also made the ornate frame for the painting.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12: Pennsylvania coat of arms by John Fisher (1736–1808), York, York County, Pennsylvania 1796. Oil on panel. H. 38, W. 39-3/4, D. 2-1/2 in. York College of Pennsylvania.

|

The final discovery presented in the exhibition is an extraordinary kitchen cupboard from Berks County (Fig. 13). When this object appeared at auction in 2008, the paint was so pristine that it almost seemed too good to be true.13 With help from Winterthur's head furniture conservator Mark Anderson and senior scientist Dr. Jennifer Mass, analytical study determined that its brilliant decoration was indeed original and the vibrant palette was identified as a red lead ground with vermilion decoration. The maker was revealed by an inscription in German script on one of the backboards, "Jacob A Blatt / 1848." A lifelong resident of Berks County, Blatt (1801-1878) was probably at work by the early 1820s; he is listed in the 1850 census as a cabinetmaker. In sharp contrast to the painted decoration are the striped maple fronts on the five small drawers. The shelves in the upper section have grooves and a rail for the display of dishes; notches cut in the front of the middle shelf are for holding spoons. The doors of the lower section flank a central scrolled bracket reminiscent of those used on the fronts of pillar-and-scroll chests of drawers. On the back of the cupboard, a section of paint on the lower case shows how Blatt experimented with the color and graining technique before applying it to the primary surfaces.

|

Many more discoveries are presented in the Paint, Pattern & People exhibition and accompanying publication, where numerous examples of well-documented furniture provide a foundation on which to build new interpretations of the region's furniture and people. Hopefully, this work is only the beginning of an ongoing discussion. Eighty-six years after the publication of Esther Stevens Fraser's article on Pennsylvania German painted chests, her words remain as true as ever. For more information on the exhibition and publication call 800.448.3883 or visit www.winterthur.org/sepa. The catalogue is available from www.winterthurstore.com.

|

|

|

Wendy A. Cooper, the Lois F. and Henry S. McNeil Senior Curator of Furniture at Winterthur Museum, and Lisa Minardi, the Assistant Curator of Furniture for the Southeastern Pennsylvania Furniture Project, are co-authors of the accompanying publication Paint, Pattern & People: Furniture of Southeastern Pennsylvania, 1725–1850.

|

|

|

1. Esther Stevens Fraser, "Pennsylvania Bride Boxes and Dower Chests, Part II: County Types of Chests," The Magazine Antiques 8, no. 2 (August 1925): 84. ↑

|

2. Thomas Coulson will and inventory, no. 2087, Chester County Archives. Inventory and estate sale of John Coulson, 1812, Cecil County Register of Wills (Inventories), vol. 16, 57–60, Maryland State Archives. ↑

|

3. The top section of another line-and-berry inlaid desk-and-bookcase (privately owned) has survived without its base; see Pennypacker Auction Centre, Important Americana Antique Sale: The Renowned Collection of Perry Martin, http://www.antiquesandfineart.com/articles/media, Pa., May 26, 1969, lot 201. ↑

|

4. Margaret Berwind Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 40, pls. 7–8. ↑

|

5. Jacob Brown inventory and vendue, 1802, Cecil County Register of Wills, vol. 12, 481–486, Maryland State Archives. An article on the Nottingham school of cabinetmaking and Jacob Brown by Wendy A. Cooper and Mark J. Anderson will appear in the 2011 volume of American Furniture.↑

|

6. Inventory of James Murray, 1747, Lancaster County Historical Society. ↑

|

7. The Minnich chest was sold at Skinner's, American Furniture and Decorative Arts, Boston, Mass., Nov. 4–5, 2006, lot 700. ↑

|

8. The Grim chest is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, acc. no. 25–93–1. ↑

|

9. With thanks to William Woys Weaver for the identification of these designs. ↑

|

10. Eliza Cope Harrison, ed., Philadelphia Merchant: The Diary of Thomas P. Cope, 1800–1851 (South Bend, Ind.: Gateway Editions, 1978), 13. ↑

|

11. Carl Bridenbaugh, The Colonial Craftsman (New York: New York University, 1950), 56. ↑

|

12. York County Heritage Trust, County Commissioners records, 1796, no. 82. With thanks to Becky Roberts, Merri Lou Schaumann, and June Lloyd for their assistance in finding this record. ↑

|

13. The cupboard was sold at Pook & Pook, The Americana Collection of Richard and Rosemarie Machmer, Downingtown, Pa., October 24–25, 2008, lot 271. ↑

|

|

|

|

|

|