|

|

|

|

|

BY MEGAN HOLLOWAY FORT

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954),

Blue Nude, 1907.

Oil on canvas, 36¼ × 55¼ inches.

The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland, BMA (1950.228).

© 2013 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photography by Mitro Hood.

|

For the past hundred years the International Exhibition of Modern Art has been considered a signal event in the history of American art. Now known as the Armory Show, it was mounted by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (A.A.P.S) in New York at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, between East Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Streets, from February 17 through March 15, 1913, and introduced avant-garde European art to an American audience. Some 1,400 works—paintings, drawings, prints, sculpture, and decorative objects by European and American artists—drew approximately 87,000 visitors, and sparked an impassioned debate over the nature and future of modern art that played out in the press, as well as in meeting rooms, drawing rooms, and dining rooms across the country. Portions of the exhibition later traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Copley Society in Boston.

|

|

|

|

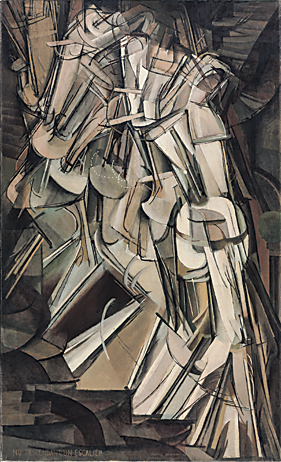

Fig. 1: Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887–1968),

Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912.

Oil on canvas, 57⅞ × 35⅛ inches.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection (1950, 1950–134–59).

© 2013 Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

Fig. 2: Constantin Brancusi (Romanian-French, 1876–1957),

Mademoiselle Pogany, 1912–1913.

Plaster, 17¾ × 9 inches.

Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Reunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photography by Philippe Migeat.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Odilon Redon (French, 1840–1916),

Silence, ca. 1911.

Oil on prepared paper, 21½ × 21¼ inches.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection.

Digital Image

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

|

The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution, an exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, commemorates the centenary of the Armory Show and reassesses it, using a group of about one hundred works that reflect the unprecedented range of the 1913 event. Included are paintings, sculpture, and works on paper that represent the scandalous European avant-garde and the range of early-twentieth-century American movements that the original show highlighted. Also included are examples of the historical works the organizers hung to show the progression of modern art leading up to the controversial abstract works that have become the Armory Show’s hallmark.

No work of art is more closely identified with the 1913 Armory Show than Marcel Duchamp’s iconic Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (Fig. 1), which intrigued American audiences more than any other work on display. The A.A.P.S. president, Arthur B. Davies, and secretary, Walt Kuhn, the exhibition’s co-organizers, first met Duchamp and his artist brothers—Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon—in November 1912 in Paris. They traveled there from New York to work with their European agent, the American painter Walter Pach, to select works for the show.1 They chose four works from the Duchamp brothers’ studio.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890),

Mountains at Saint-Rémy (Montagnes a Saint-Rémy), 1889.

Oil on canvas, 28¼ × 35¾ inches.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection,

Justin K. Thannhauser (1978, 78.2514.24). |

Although Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were well known as the originators of Cubism in Europe, the Nude Descending became the symbol of the movement in the American debate over the avant-garde, generating an overwhelming amount of hostile criticism. A common complaint among conservative critics was the seeming inconsistency between the title of the work and its imagery. Locating the nude became such a joke in the press that the American Art News offered $10 to any reader who in fifty words could solve the “Armory Puzzle.”2

The Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Brancusi was another artist whose work was reviled by the press. Among the five works the organizers selected from his studio was Mlle. Pogany (Fig. 2), an abstracted representation of the Hungarian art student Margit Pogány, whom Brancusi sculpted in Paris in December 1910–January 1911.3 Introducing abstracted, nonliteral representation into the sphere of sculpture, Brancusi’s extreme simplification of form was new to most visitors, who were accustomed to sculpture like the American examples on view—traditional, representational, and conservative. The critic for the New York Herald (on February 17, 1913) described Mlle. Pogany as “a piece of sculpture that looks like an underdeveloped and deformed infant.” Many other reviewers compared the figure’s head to an egg.4 But some appreciated Brancusi’s innovations. Robert Chanler, the artist whose painted screens were also a great success at the exhibition (see Fig. 7), purchased a bronze version of Mlle. Pogany for $550.5

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (French, 1824–1898),

Le Verger, Les Enfants au verger, L’Automne, ca. 1885–89.

Oil and pencil on canvas, 31½ × 39 inches.

The City College of New York. |

Henri Matisse was another popular target in the press. The reaction to his Blue Nude (Fig. 3), one of his most important works, bordered on violent. Though the critics felt baffled by the Cubists, in general they recognized that their art reflected some degree of technical and intellectual progress. The distorted forms, erratic color, and crude technique of Matisse and his fellow Fauves, on the other hand, seemed like a deliberate step backward, “wanton perversity” in the words of one critic.6 Therefore, while Cubism provoked laughter and satire, Matisse engendered anger and a fear of societal regression. Writing in The International in April 1913, reviewer J. Nilsen Laurvik aptly summarized the critical response: “It was a long step from Ingres to Matisse, but a very short step from Matisse to Anger.” Antagonism to Matisse’s work peaked when the Armory Show traveled to its Chicago venue, where a group of students at the Art Institute burned works by the artist in effigy.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Robert W. Chanler (American, 1872–1930),

Leopard and Deer, 1912.

Gouache or tempera on canvas, mounted on wood,

76½ × 52½ inches. Rokeby Collection.

Photography by Glenn Castellano. |

Yet some European works received a warm reception, especially the French printmaker, draftsman, and painter Odilon Redon.7 Before the exhibition, Redon was little known in the United States; Kuhn first encountered a collection of his paintings and pastels on view in The Hague in October 1912.8 Captivated by their surreal quality and opulent color (Fig. 4), he secured thirty-nine oils, pastels, and charcoal drawings and large number of prints. On December 12, 1912, Kuhn wrote to Pach: “We are going to feature Redon big (BIG!).”9

Kuhn was right. Redon’s expressive use of color and poetic and mysterious imagery made his work a hit, even among conservative critics such as Frank Jewett Mather Jr., who, in The Nation (March 6, 1913), described it as “fantastically beautiful art, very far from life, admirably true to its own vision.” Brisk sales of Redon’s work—including some thirteen paintings and twenty prints—are further evidence of the public’s enthusiastic reception.10

The Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh was one of the most eagerly anticipated of the artists whose works were to be seen at the Armory Show. This was fueled both by interest in his personal history—mental illness, institutionalization, and dramatic death—and by his growing reputation in the United States as a groundbreaking painter.11 Mountains at Saint-Rémy (Fig. 5), formerly known as Collines à Arles or Hills at Arles, was painted shortly after Van Gogh had committed himself to the hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in the southern French town of Saint-Rémy. During his year-long stay, the clinic and its grounds became his primary subject. The view in the painting is of the Alpilles, a low range of mountains visible from the hospital grounds. The canvas features the heavy impasto and bold, strong, swirling brushstrokes characteristic of his late work.

|

|

|

Fig. 8: J. Alden Weir (American, 1852–1919), The Factory Village, 1897.

Oil on canvas, 29 × 38 inches.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Cora Weir Burlingham, 1979, and Purchase, Marguerite and Frank Cosgrove, Jr. Fund, 1998 (1979.487). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 9: Ethel Myers (American, 1881–1960),

Portrait Impression

of Mrs. D. M., 1913. Bronze,

9½ inches high.

Collection of Nan and David Skier, Birmingham, Ala.

|

One of the goals for the 1913 exhibition was to educate viewers on the evolution of modern art—from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Courbet to the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Cubists. To that end, a number of historical works were shown, and the organizers devised a “Chronological Chart Outlining the Growth of Modern Art.” Published in Arts & Decoration (March 1913), it showed how the last hundred years of art displayed a clear progression, as one innovation led to another. The outline was meant to legitimize the new and to demonstrate that many artists whose work once seemed outrageous had a later history of being acclaimed.

Among the historical painters the organizers highlighted was the French muralist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who made his reputation in the nineteenth century by pioneering radical, innovative aesthetic constructs while working with classical and religious imagery. Puvis was already well known in the United States in 1913: his work was reproduced in American publications, exhibited in galleries and museums, and collected by those seeking art in an inventive but acceptable modernist style. Le Verger, Les Enfants au verger, L’Automne (Fig. 6) was among fifteen of his paintings and drawings on view and the poetic, pastoral scene is typical of the artist’s mature work.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10: Joseph Stella (American, 1877–1946),

Still Life, 1912.

Oil on canvas, 23¼ × 28¼ inches.

Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis, Minn. |

Largely overshadowed by the European avant-garde were the over six hundred paintings, drawings, watercolors, prints, and sculpture highlighting the newest tendencies in American art, despite the organizers’ requests to their colleagues for “examples of your most advanced work.”12 Among those represented were twenty-three A.A.P.S. members, one hundred non-members who were invited to participate, and about sixty men and women who were not invited but had works accepted after examination by the Domestic Art Committee.

Standing at the entrance to the exhibition was a group of ten elaborately painted screens by the American artist Robert Chanler, who is little known today but was one of the most acclaimed artists at the Armory Show. Born to a distinguished family descended from Astors, Delanos, Stuyvesants, and Livingstons, Chanler studied art in Rome and Paris before settling in New York. In 1902, he purchased a townhouse on East Nineteenth Street that he decorated with his own work and that became a social center for New York’s art community. Stimulated by his so-called House of Fantasy, Chanler’s friends began to commission elaborate murals and painted screens for their own residences and for the exclusive Colony Club in New York.

Chanler’s family has said he painted Leopard and Deer (Fig. 7) in homage to “a ferocious ex-wife,” probably Julia Chamberlain, whom he divorced in 1907.13 A replica of the screen was available for purchase from the Armory Show for $1,200. It was also one of the fifty-seven works that the A.A.P.S., taking a cue from the 1912 Sonderbund Exhibition in Cologne, Germany, reproduced and sold in postcard form at the exhibition.

The American Impressionist painter Julian Alden Weir also received high praise, and his role in the A.A.P.S. is an interesting side note. Throughout his career Weir was active in artist associations, including the National Academy of Design, the Society of American Artists, and the Ten American Painters. In late 1911 he was elected president (in absentia) of the newly founded A.A.P.S. While Weir supported the Association’s stated purpose of improving exhibition opportunities for younger artists, he was surprised to read in the New York Times (January 3, 1912) just days after his election that the group was “openly at war with the Academy of Design.” He immediately resigned and asserted his loyalty of the Academy, writing in an open letter that appeared in the New York Times on January 4 that he had “attended no meetings of this society” and was thus misinformed of its intentions. Nevertheless, Weir sent seven oil paintings and several etchings and watercolors to the Armory Show, among them The Factory Village (Fig. 8), which depicts the massive mid-nineteenth-century cotton mills of the Willimantic Linen (later American Thread) Company, situated along the Willimantic River near Weir’s farm in Windham, Connecticut.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11: John Marin (American, 1870–1953), Woolworth Building, No. 28, 1912.

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 18½ × 159⁄16 inches.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. © 2013 Estate of John Marin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

|

Fifty women exhibited their works at the Armory Show. One was the American sculptor Ethel Myers, whose husband Jerome Myers was a member of the A.A.P.S. A native New Yorker, she studied painting under Robert Henri and embraced his exhortations to depict contemporary life. In 1906 she began creating the small-scale statuettes for which she is best known. Modeled in wax or clay, her sculptures included commissioned portraits of society women, as well as depictions of various urban types—shop girls, performers, matrons, cleaning women, and fashionable ladies about town. Nine of Myers’ works in the Armory Show were selected from an exhibit of her statuettes at the Folsom Galleries in New York in late 1912.14 Portrait Impression of Mrs. D. M. (Fig. 9) was lent by its subject, Mrs. Daniel H. Morgan, who, with her husband, were active collectors of modern art; he made the first purchases at the Armory Show, three Redon paintings.15

The Italian-born New York painter Joseph Stella was among the American artists who were not invited to participate in the show but gained admission through the Domestic Art Committee. Stella was also one of the first Americans to fully assimilate the language of modern art into his work. In Europe from 1909 to 1913, where he admired the work of Paul Cézanne and met Matisse, Picasso, the Italian Futurist painter Gino Severini, and the influential collector Gertrude Stein, by 1911 he was painting a series of Post-impressionist still lifes, including Still Life (Fig. 10), that incorporated the Fauvists’ high-keyed color and textured surfaces and Cézanne’s treatment of three-dimensional space.

Perhaps the most radical of the American works in the Armory Show were the six watercolors by John Marin depicting New York City skyscrapers. The Woolworth Building (Fig. 11) was itself a symbol of modernity in New York. Designed by the American architect Cass Gilbert, it was the tallest building in the world when it opened in 1913. At the Armory Show, Marin exhibited a series of four views of the building that show a progression from naturalistic depiction to abstraction. Compared in the press to “an earthquake” (New York Times, March 2, 1913), and described as “an attempt to show, not the building primarily but its effect on the feelings of the viewer” (New York Evening Sun, February 18, 1913), Marin’s watercolors of a destabilizing Woolworth Building show the direction that some American artists would pursue in the wake of this seismic event.

|

|

|

|

The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution is on view at the New-York Historical Society through February 23, 2014. A fully illustrated exhibition catalogue (D. Giles; $79.95) is available. For information call 212-873-3400 or visit www.nyhistory.org. The New-York Historical Society recognizes lead sponsor Harold J. and Ruth Newman for their exceptional commitment to The Armory Show at 100. Generous support has also been provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Lily Auchincloss Foundation, Inc. Support for the development of The Armory Show at 100 online resource has been provided by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. |

|

|

|

The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution, organized by Kimberly Orcutt and Marilyn Satin Kushner, is on view at the New-York Historical Society from October 11, 2013 to February 23, 2014; this is the only venue. The accompanying publication (D. Giles; $79.95), which includes contributions by twenty-four prominent scholars, is available through the N-YHS by phone at 888.860.6947, or online at www.nyhistorystore.com. |

|

|

|

|

Megan Holloway Fort, Ph.D., is an art historian who contributed research and writing to The Armory Show at 100.

|

|

|

|

1. Pach was part of the circle surrounding the influential patrons Gertrude and Leo Stein. He moved among the Parisian avant-garde, exhibiting with them and immersing himself in their new artistic vision, and was thus well positioned to help secure loans of contemporary French work.

2. “The Armory Puzzle,” American Art News 11, no. 21 (March 1, 1913), 3.

3. The works were Le Baiser, now titled The Kiss, 1907-08, plaster, location unknown; Muse endormie, now titled Sleeping Muse, 1911, plaster, Private Collection; Une Muse, now titled The Muse, 1912, plaster, location unknown; Mlle. Pogany, 1912, plaster, Musée National de l’Art Moderne, Paris; and Torse, now titled Torse de femme, 1912, marble, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Germany.

4. See, for example, Maurice Morris, “At the International Art Show,” The Sun (New York) (February 23, 1913), 10.

5. Chanler had wanted to buy a version in marble, but it was too expensive. See Marielle Tabart et al., La Dation Brancusi: Dessins et Archives (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2003), 102–103.

6. “Ultra Moderns in a Live Exhibition at 69th’s Armory,” New York Evening Mail (February 17, 1913), 8.

7. See “American Pictures at the International Exhibition Show Influence of Modern Foreign Schools,” New York Times (March 2, 1913), SM 15; “International Art,” New York Evening Post (February 20, 1913), 9, among others.

8. Milton Brown, The Story of the Armory Show, 2nd. ed. (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 67.

9. Quoted ibid., 78.

10. Thirteen of his paintings and pastels and twenty prints were sold to collectors, including Daniel Morgan, John Quinn, and Lillie P. Bliss, who purchased Silence for $540. The artists and Armory Show exhibitors Katherine Dreier and Robert Chanler purchased Redon lithographs, and the critic Harriet Monroe bought one in Chicago. See Brown, 120–121, 129, 131, 213.

11. Van Gogh died of two gunshot wounds to the chest, which most scholars believe to have been self-inflicted despite the fact that a gun was never found in the artist’s possession.

12. See Virginia M. Mecklenburg, “Slouching Toward Modernism: American Art at the Armory Show,” in The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution, Kimberly Orcutt and Marilyn Kushner, eds. (New York: New-York Historical Society, 2013), 243–61. Many artists brought more than one painting.

13. The legal battle was documented in a series of articles in the New York Times in September–October 1910.

14. Ethel Myers Papers, 1913–1960, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, microfilm reel N68-6, frame 42. The other works by Ethel Myers included in the Armory Show were: The Matron, 1912; Fifth Avenue Gossips; Fifth Avenue Girl, 1912; Girl from Madison Avenue, 1912; The Widow; The Gambler, 1912; Upper Corridor; and The Duchess.

15. Brown, 120. |

|