|

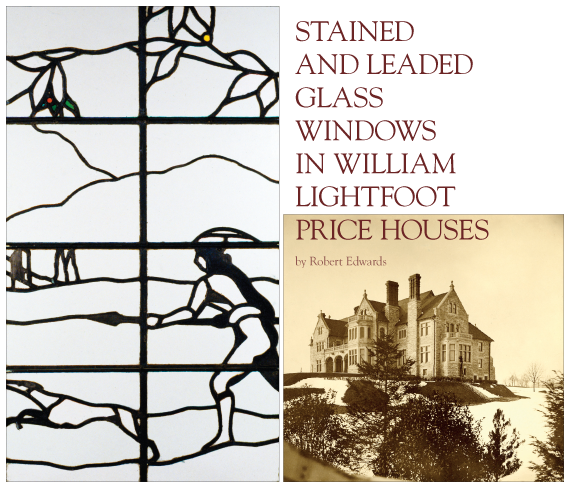

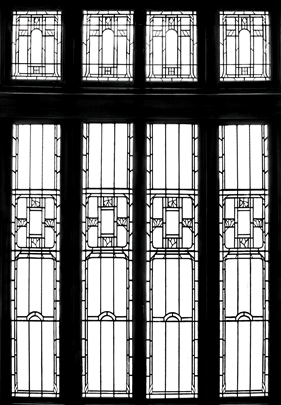

| Fig: 1a: William Lightfoot Price (1861–1916), Stained glass window, ca. 1905. Leaded glass, oak. H. 40, W. 24 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Jane D. Kaufmann Gift and Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1993 (1993.6.3). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Source: Art Resource, N.Y. |

|

Fig: 1b: Period photograph, Frank van Camp house, 1905, Indianapolis, Indiana. Courtesy, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia. The “hunt series” of windows now displayed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art are catalogued as being from the Van Camp house, which was built from Price designs. The house has been demolished, making it difficult to understand how the architect related the highly stylized designs of the hunt windows to the robber-baron historicist designs of his buildings.

|

|

|

|

Rose Valley, a community established in 1901 just outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, exists as a rare and highly significant American Arts and Crafts movement experiment in utopian living. Architect William Lightfoot Price (1861–1916) was the primary founder and driving force in the development of the community; thus many of his designs for buildings, furniture, and leaded glass have been placed within the framework of the movement, which many scholars believe started in America at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.1 The stained-glass windows attributed to Will Price now displayed in museum galleries—where they are isolated from the grand, elaborate mansions in which they were originally installed—are surrounded by objects produced during the era when the Arts and Crafts movement had its greatest impact on America (Figs. 1a–b). This context makes the windows appear to be an expression of modernist aspects of the movement. In fact these windows should not be burdened with an Arts and Crafts context nor should their design be attributed to Price.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2a: Frank Lloyd Wright’s (1867–1959) home and studio, west façade, Oak Park, Illinois, 1889–1898. Courtesy, Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust; photography by Don Kalec.

|

|

Fig. 2b: William and Frank Price’s designs for the Wayne, Pa.,

tract development started in 1883 bear many similarities with Wright’s early houses such as his home and studio shown in figure 2a, including the use of diamond-paned windows to enliven exterior textures; the patterns in the original Price windows are now obscured by storm windows.Photography by the author.

|

|

Will Price’s ideas about organic architecture as applied to some of his domestic buildings were as progressive as those of his peer Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), and their manifestation was specific to their locations, which was most often Southeastern Pennsylvania. Materials indigenous to Pennsylvania, like the fieldstone, timber, and tile used on Price’s rambling Thunderbird Lodge built in Rose Valley 1904, would look incongruous in Oak Park, Illinois, just as the long, low Prairie School lines of Wright’s 1905 yellow brick Darwin Martin house look out of place in suburban Buffalo, New York. However, none of the houses Price designed for Rose Valley have leaded, stained-glass windows; he seems to have specified such windows for larger, fancier houses built on suburban lots outside the valley.

Wright’s leaded windows are often interpreted as an avant-garde departure from the late-nineteenth-century norm as are a limited number of Price windows. The way each designer used such decorative glass has, I think, more to do with regionalism and the length of their careers than it has to do with modernism. Both architects began their careers when the Arts and Crafts movement, which purported to honor a concept of truth to materials, was beginning to have an impact in America (Figs. 2a, b). Price spent his career in the Philadelphia area, where historicism was a valued element of turn-of-the-century design. He was active for a relatively short time because he died in 1916, when the effects of the movement were still current but waning. Wright lived in Wisconsin and later in Arizona where the spirit of modernism was pervasive. He was active until he died in 1959, giving him many years to evolve to the point that he could plunk the fantastic futuristic Guggenheim museum building in the middle of New York City’s merely modern skyscrapers. The titan of stained-glass design in America, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), lived and worked in New York during the Arts and Crafts era, although he didn’t freight his production with Arts and Crafts theories. A comparison of the ways these three designers used stained and leaded glass sheds a new light on Price windows.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

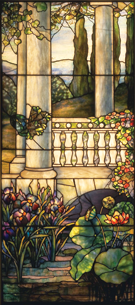

Fig. 3a: Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), Tiffany Studios (1900–1932), Window Panel, 1908–1912. Leaded glass. H. 70, W. 31-1/4 inches. Gift of Loyalhanna Foundation. Photography by Tom Little. Courtesy, Carnegie Museum of Art (70.47.3). Tiffany windows can lead one into a fantasy world by obscuring the real world hidden beyond opaque glass.

|

|

Fig. 3b: Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), Sumac window, 1902–1904, Dana-Thomas House, Springfield, Illinois. Courtesy, Dana-Thomas House and Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Photography by Doug Carr. Wright characteristically integrates the real world with his designs by using large areas of clear glass.

|

|

Fig. 3c: Price combined the fantasy of subject with the real world, using medieval themes drawn with wide lead cames and filled with transparent colored glass. 1904 George S. Graham house, “Glenmeade,” Bryn Mawr, Pa. Photography by the author.

|

|

Tiffany was fascinated with simulacrum. As illustrated in figure 3a, aesthetic details such as the shadings and undulating surfaces of flower petals were mimicked in his works. His designers layered sheets of glass in order to suggest depth and perspective and even tried to replicate solid marble temples with delicate, nacreous translucent glass. Although Tiffany’s windows seldom relate to Gothic stained glass stylistically, like Medieval artisans, his workshop used many lead cames to assemble vast windows from small pieces of glass. Tiffany’s windows are seldom an integral part of a building’s architecture—from the inside, one looks past the walls of the buildings his windows decorate into heavenly or naturalistic imaginary landscapes where glass flowers bloom in an eternal spring. Tiffany himself did not design every window, but most were made at Tiffany’s workshops.

Wright’s windows are part of his architecture (Fig. 3b). From the outside, they add glittering textural complexity; from the inside, they modulate without obscuring one’s experience of the actual natural light and landscape. The diamond-paned windows in his early houses are not much different from those in Price-designed houses or those designed by their many less-distinguished contemporaries; their evolution into his later “light screens”2 seems more inevitable than innovative. As with Tiffany designs, Wright designs use natural plant forms (sumac, wisteria, hollyhocks), but their effect is very different. The size of the glass pieces was not restricted by the method of manufacture, and the geometric pattern of the metal cames, which hold the glass together, is integral with the design of the whole house. Wright established the motif for each house, but he did not always design the windows, and they were manufactured at several different workshops.

Some of the windows Price used in his early houses are very nearly generic for their era, but some he specified for his grand mansions (Fig. 3c) depart from naturalistic Tiffany windows and geometric Wright light screens. In as much as any of the three designers worked in the Arts and Crafts style, Price’s windows, with their heavy lead lines and lack of perspective, fall into the aesthetic described by John Ruskin (1819–1900) and William Morris (1834–1896), which encouraged the use of schematic or two-dimensional designs instead of those that relied on shading and perspective to create an illusion of reality.

|

|

|

Fig. 4a: Previously attributed to William Price (1861–1916). Leaded glass; white oak frame. H. 28-1/4, W. 46-3/8, D. 1-7/8 in. 1974-146-7. Purchased with the Thomas Skelton Harrison Fund, 1974. Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art. This hunt window is one of a series of seven windows originally installed at “Yorklynne,” the John O. Gilmore house, Merion, Pa, 1899.

|

|

|

|

|

Figs. 4b and 4c: Image for figure b is comprised of portions of two windows spliced together for illustration purposes. Morgan Jones house, 1906, Hudson, New York, designed by Marcus Reynolds (1869–1937). Courtesy, The Inn at Hudson; photography by Peter Aaron/ Esto. The suite of eight hunt windows all date before 1912, but their subject and composition relate to D’Ascenzo designs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

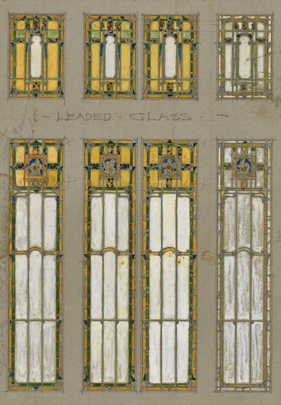

Figs. 4d and 4e: Drawings of windows for Theodore Swann house, designed by Warren Knight and Davis in 1927 and built in Birmingham, Alabama, nearly two decades after the Gilmore, Van Camp, and Jones houses. Courtesy and photography, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

|

Two sets of windows now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 4a) and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1a) are attributed to Will Price because they came from Price-designed houses. They were obviously designed by the same person, but another identical set still in a house with no known connection to Price offers an opportunity to consider a different attribution.

The windows at the Philadelphia Museum of Art came from “Yorklynne,” the John O. Gilmore house that was built in Merion, Pennsylvania, in 1899 (fig. 4a). The windows now at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 1a) are said to have come from the Frank van Camp house (figs. 1a–b) built in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1905. The third set of windows (Figs. 4b–c), remain in the 1906 Morgan Jones house in Hudson, New York; the house was designed by Marcus Reynolds (1869–1937).

The two demolished Price houses were built of grey stone and were similarly French Gothic in style, while the red brick Reynolds house has elements of seventeenth-century British and Dutch architecture as befits a house on the Hudson River. All three houses incorporated stained-glass windows of widely divergent styles; the simple, stylized “hunt windows” being the least consistent with the elaborate architectural style of each house. According to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Yorklynne hunt windows were used in the stable because they reflected Gilmore’s interest in the sporting life.3 Although the design may have been selected to reference Gilmore’s interests and the proportions were custom designed specifically for Yorklynne, the hunting theme was not unique to the Gilmore stable. The Van Camp windows (fig. 1a) have different proportions; they too may have been in an outbuilding or even in the 1910 house Price designed for Frank van Camp Jr, also in Indianapolis. Because both van Camp houses and the Gilmore house no longer survive, and hunt windows do not appear in existing architectural drawings, it is difficult to determine their original placement. Because the Jones/Reynolds house still stands, however, the location of the hunt suite windows are known: mounted as clerestory or transom windows above larger windows in the dining room of the main house, where many stained-glass windows of varied styles decorate other rooms. As to the theme of the windows reflecting the interests of the original owner, Jones was not known to have been a sportsman.

|

|

|

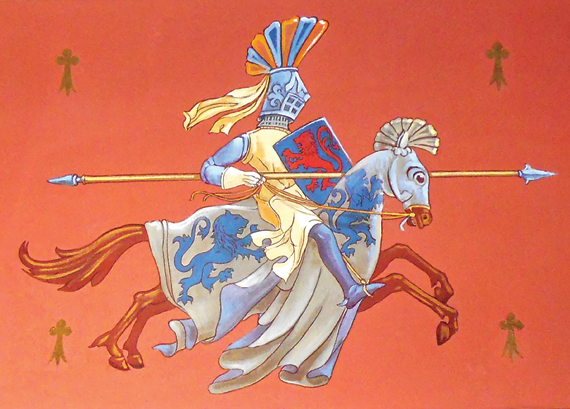

Fig. 5a: Price used medieval themes like the knight William van Ingen painted on a ceiling of the 1904 George S. Graham house, “Glenmeade,” Bryn Mawr, Pa, in many other houses, including the Gilmore house (4a).

|

|

|

Fig. 5b: The stained-glass knight is one of a pair of windows that flanks the front door of Price’s 1901 Louis Clarke House. Photography by the author.

|

Price business letters suggest that he himself did not design the hunt window series, but we cannot yet confirm the name of their designer. However, we do know the names of stained-glass designers associated with other widows used in Price houses, one of whom was William Brantley van Ingen (1858–1955). Van Ingen was born in Philadelphia and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art before moving to New York to apprentice under famed stained-glass designers John LaFarge and Louis Tiffany. Van Ingen was responsible for the designs of murals and some of the stained glass in Price’s George S. Graham house (now called “Glenmeade”) built in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania in 1904 (Fig. 5a).4 The style of the Graham murals is the same as that of the murals Van Ingen painted in the earlier Gilmore house and of murals in several other Price houses built during the same decade. Van Ingen’s style is most often realistic and romantic, relying heavily on Arthurian legend as advocated by William Morris (Fig. 5b). But Van Ingen did not make all the windows he designed; Heinigke and Bowen of New York made the windows for the Graham house. The firm Heinigke and Bowen had also been asked to provide a quote for the design and production of leaded glass in transoms for the Van Camp house living room. Period photographs of the exterior of the house suggest, however, that their leaded glass was not ordered. It is unknown whether the Van Camp hunt series was purchased in its place (though it is not in a transom format), or in what part of the house or its outbuildings they were installed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figs. 6a and 6b: The aesthetic of Nicola D’Ascenzo (1871–1954) is evident in two windows he made for the Rose Valley house Walter Price renovated with his wife during the first few years after their marriage in 1906. D’Ascenzo used floral motifs again in the later “light screens” he designed for William Price’s 1911 Wheeler house (Figs. 7a–b). Today, the Rose Hedge windows seem to look back to British designs from the end of the nineteenth century. Photography by the author.

|

|

Another mural and stained glass artist with Price associations is Nicola D’Ascenzo (1871–1954), who came to the United States in 1882. He established a studio in Philadelphia in 1893, where he specialized in portraits and murals. He seems to have acquired almost instant recognition, winning a medal at the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893, among many other awards. He met the brothers Price (architects William, Walter, and Frank) sometime around 1888 while at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art. The four were fast friends by 1906 when Walter married Felicia Thomas and D’Ascenzo made two windows for the couple’s first house “Rose Hedge” in Rose Valley (Figs. 6a–b).5 These two windows have roses conventionalized in the simple style associated with Arts and Crafts design, and were most likely conceived by D’Ascenzo himself. The wide lead cames that form stems and thorns and the stylized flower blossoms relate to windows the D’Ascenzo studio made for Will Price’s Frank Wheeler house on which construction started in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1911 (Figs. 7a–b). In a 1913 letter to Wheeler, Price wrote, “As to the leaded glass, we designed the glass for the place...” This reference to “we” does not necessarily mean Price himself designed the Wheeler windows. In the same letter Price refers to furniture designs and draperies that were to be provided by the Tobey Company of Chicago as part of a total scheme made up by “Mr. Robertson and myself…” An article in The International Studio credits these “fitments” to Tobey’s Lionel Robertson.6 Period photographs show that most of the wood-frame upholstered furniture was designed by Tobey artists in that company’s distinctive style, which I interpret as evidence that artisans did not always follow specific Price designs.

|

|

|

|

|

Figs. 7a and 7b: The hall window from the 1911 Wheeler house, Indianapolis, Indiana, seems to foretell art deco design, especially as D’Ascenzo first envisioned it on paper (7a). The small arches that march across the centers of the four long panels in the Wheeler window are idiosyncratic devices peculiar to Will and Walter Price and, as such, they may be a measure of the architect’s involvement with the design process. 7a: Courtesy and photography, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia; 7b: Courtesy Marian University; photography by Benjamin L. Ross, LEED AP BD+C.

|

|

The output of D’Ascenzo’s studio was vast, and the widely varying styles would be expected because he accepted commissions from different architectural firms, but it was usual for windows to be designed “in-house” by the army of artisans he employed to keep up with production. A D’Ascenzo card catalogue, now at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, which houses both the extensive D’Ascenzo archive and much of Price’s architectural archive, lists a number of jobs for Price, although the Gilmore and Van Camp commissions do not seem to be among them. Many of the hundreds of D’Ascenzo designs held by the Athenaeum used standardized motifs that could be adapted to a client’s interests; among them is a caravel design (Fig. 8a, detail): A “caravel” was a diminutive sailing vessel that often had visually dramatic lanteen rigging with triangular sails; these ships were widely used for trade and exploration during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, perhaps most famously by Christopher Columbus. The caravel was a favorite Arts and Crafts motif that remained in use well into the 1930s. Also among the known D’Ascenzo studio commissions is a set of windows made for the Theodore Swann house built in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1929 (fig. 4 d–e).7 The Swann windows are rendered in a realistic style characteristic of 1920s and 1930s Tudor Revival, which was often more pedantic than the earlier Tudor style of Price’s interiors for the Van Camp, Gilmore, and Graham houses. But segments of the Swann windows incorporate compositions that arrange stag, hunter, and hound motifs so they cross from panel to panel in a manner that very closely resembles designs in the hunt series used by both Price and Reynolds (figs. 4a–c). A sailing ship in whaling scenes (Fig. 8b) installed with the hunt series in the Jones house is a slight variation of the caravel transom designs D’Ascenzo exhibited in 1912 (Figs. 8a, detail).8 As noted, Reynolds also chose a suite of hunt window transoms for the Jones house (Figs. 4b–c; 8e–g). Since the Jones caravel transom is obviously from the D’Ascenzo studios, it is reasonable to assume that the Jones hunt series is also by D’Ascenzo and, by extension, those in Will Price’s Gilmore and Van Camp commissions may be the work of the same designer.

In addition to the shared motifs, the Gilmore, Van Camp, Jones, and Swann windows all exhibit a distinctive D’Ascenzo characteristic, which he described in an article called “Principles and Tendencies in the making of Ornamental Stained Glass” written for The Ornamental Glass Bulletin in 1924: “The more you submerge the black lines of lead and iron, the worse the window. Lead is not only necessary to separate the glass pieces and define the color and design, it adds brilliancy and sparkle to the window and is as necessary as its brightest color.”

|

|

|

Fig 8a

|

|

|

Fig 8a, detail

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8b, detail

|

ABOVE: Figs. 8a–g: While the caravel window in the Jones house series (8b, detail) is almost identical to D’Ascanzo’s painting (8a, detail), the Jones windows (8b–g) additionally include depictions of whaling activities (8c–d), which were important to the Hudson River community where the house is located. If the Jones whaling series can be attributed to D’Ascenzo, it is possible that the Jones hunt series (4b–c; 8e–g) is also from the D’Ascenzo studios, although I would argue for a Heinigke and Bowen attribution. 8a: Courtesy and photography, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia; 8b–g: Courtesy, The Inn at Hudson; Photography by: Peter Aaron/ Esto.

|

The Philadelphia Museum of Art describes Price as the designer of the Gilmore hunt series, and states that he was one of few Americans designing windows that incorporated continuous lines of leading in an “avant-garde design, which shows the influence of Continental Art Nouveau as well as the English Arts and Crafts movement.”9 Price seldom drew specific window designs into his highly detailed elevations, and I have not yet found window designs in his very extensive archive that relate to the hunt series. While the use of lead lines to unify a design from window to window was widely employed by American, British, and European artists, evidence suggests that the leading in the hunt windows is consistent with D’Ascenzo’s preferred technique, which in many instances relies on heavy lead lines more than colored glass to “draw” designs. D’Ascenzo kept such designs in stock and supplied them to architects for houses that were built decades after the Gilmore windows were installed. In every instance that I’ve seen, the leaded windows (excepting skylights) Price selected use large areas of clear glass, which modulate daylight without totally obscuring the landscape outside.

After the Price and D’Ascenzo archives are catalogued and more is published about Heinigke and Bowen, additional research should confirm some of my attributions, but for now it seems obvious that Will Price did not design the leaded or stained glass windows used in the houses he and his architectural firm produced. Instead, he probably chose appropriate subjects from the “better residential” stock designs provided by his friend Nicola D’Ascenzo or chose between competing bids.10

|

|

|

The author wishes to thank Bruce Laverty, Gladys Brooks Curator of Architecture, Athenaeum of Philadelphia; Jeanne Solensky, Libraian, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, and the homeowners who graciously allowed photography of the windows in their homes.

|

|

|

Robert Edwards is an independent scholar and a dealer specializing in decorative arts from the American Arts and Crafts movement.

|

|

|

|

1. William Ayers, ed., Rose Valley: A Poor Sort of Heaven, A Good Sort of Earth (Chadds Ford, Pa: Brandywine Museum of Art, 1983).

2. Julie L. Sloan, Light Screens: The Complete Leaded Glass Windows of Frank Lloyd Wright (New York, Rizzoli International Publications, 2001). The phrase “light screens” was not coined by or specific to Wright.

3. Darrell Sewell, ed., David A. Hanks, contributor, Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art, (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), 460–461.

4. George Scott Graham (1850-1931) was a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Van Ingen designed murals and stained glass for the Pennsylvania State capitol building, which was dedicated in 1906, and is perhaps best known for his murals in the 1914 Panama Canal Administration Building.

5. For a discussion of the Rose Hedge windows, see Eleanore Price Mather, “Rose Valley,” in TILLER, 1 (January/February 1983), 27–29. Eleanore was the daughter of Felicia Price, who wrote a privately printed memoir called Glimpses of 50 years in the Life of Felicia Thomas Price: “We called it [the house] ‘The Rose Hedge’ and had Nicola D’Ascenzo, a distiguished stained glass designer and friend of Walter, make a pretty stained glass side panel to our front door with the name ‘Rose Hedge’ incorporated therein.”

6. Henry Blackman Sell, “Good Taste and the Mansion” in The International Studio; 57, no. 225 (November 1915); xi–xv.

7. William Warren designed the Theodore Swann house. Swann was a Birmingham, Alabama, industrialist who commissioned D’Ascenzo windows for the Swann Chemicals buildings and the Independent Presbyterian Church.

8. Quoted in Lisa Weilbacher, “A study of Residential Stained Glass: The Work of Nicola D’Ascenzo Studios From 1896 to 1954,” MA thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1990, 60. D’Ascenzo uses the term “light screens” in the same article.

9. Sewell, Philadelphia.

10. D’Ascenzo pencil notations on original designs in the Athenaeum of Philadelphia collections include “Better Residential,” “Better Restaurants,” and “Better Banks.” A 1914 letter addressed to Heinigke and Bowen states, “We are very sorry to say that after consultation with the owner, we decided to accept the design and proposition of the D’Ascenzo Studios for the glass for the Hotel Annex at Atlantic City.” Collection 41, box 15, the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera.

|

|