|

Displaying items by tag: Cubism

The Denver Art Museum and the Clyfford Still Museum will present Picasso to Pollock: Modern Masterworks from the Albright-Knox Art Gallery from March 2, 2014 through June 8, 2014. The sprawling exhibition will bring together approximately 50 works by more than 40 significant artists from the late 19th century to the present. The show is drawn from the holdings of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, which boasts one of the finest collections of 20th century art in the country.

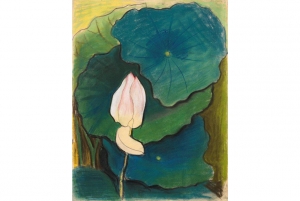

Modern Masterworks will present works by Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Georgia O’Keeffe, Salvador Dali, Frida Kahlo, Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock. The exhibition charts the evolution of modern art, starting with post-Impressionism and moving on to a number of groundbreaking movements such as Cubism, Surrealism, Pop Art and Minimalism. A large portion of Modern Masterworks is comprised of works by mid-century American artists such as Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell.

A related exhibition, 1959, will be on view at the Clyfford Still Museum from February 14, 2014 through June 15, 2014. The show re-creates Still’s seminal exhibition held at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in 1959. Still, one of the leading figures of Abstract Expressionism was a contemporary of Pollock, de Kooning, Motherwell and Rothko.

Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer Director of the Denver Art Museum, said, “Not only are most of the iconic artists of the time represented, but the works themselves are masterpieces from each artist.”

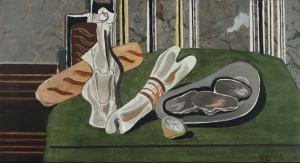

The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. is currently hosting the exhibition Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945, the first in-depth look at the Cubist master’s works preceding World War II. During this period, Braque used the theme of still life to hone his pioneering Cubist style. The exhibition presents 44 works from this period as well as related objects that help trace the artist’s evolution from a painter of still lifes to interiors in the late 1920s, to large-scales spaces in the 1930s, to personal interpretations of everyday life in the 1940s.

The exhibition brings together Braque’s Rosenberg Quartet (1928-1929) for the first time in 80 years. The four canvases were used as models for marble panels in the Paris apartment of Braque’s art dealer, Paul Rosenberg. All in varying degrees of completion, the works come together to reveal the different stages of Braque’s artistic process.

Duncan Phillips, founder of the Phillips Collection, was a well-known champion of Braque’s work and helped introduce his paintings to a wider American audience through acquisitions and exhibitions. Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945 will be on view at the Phillips Collection through September 1, 2013.

The Museum of Modern Art’s William S. Paley collection is currently on view at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine. A Taste for Modernism presents 62 works that cover all of the pivotal movements that defined the art world during the late 19th and 20th centuries. The exhibition features works by 24 major artists including Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Joan Miró (1893-1983), Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), and Francis Bacon (1909-1922). The William S. Paley collection has been on a North American tour since 2012 and the Portland Museum of Art is the only venue in New England that the exhibition will visit.

Highlights from the exhibition include two works by Cézanne, which Paley acquired from the artist’s son; eight works by Picasso that trace his artistic evolution over the first three decades of the 20th century including Boy Leading a Horse (1905-06) from his Rose Period, the Cubist painting An Architect’s Table (1912), and the collage-inspired composition Still Life with Guitar (1920); Gaugin’s The Seed of the Areoi (1892), which was inspired by the artist’s trips to Tahiti; and Edward Hopper’s (1882-1967) realist landscapes.

William S. Paley (1901-1999), the media mogul responsible for building the CBS broadcasting empire, was an important art collector and philanthropist during the 20th century. Paley began collecting in the 1930s and took a particular liking to French modernist movements including Fauvism, Cubism, and Post-Impressionism. Paley played a major role in cementing the Museum of Modern Art as one of the most significant institutions in the world. MoMA was founded in 1929 and Paley fulfilled various roles at the museum including patron, trustee, president, and board chairman from 1937 until his death.

A Taste for Modernism will be on view at the Portland Museum of Art through September 8, 2013. It will them travel to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (October 10, 2013-January 5, 2013) and The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas (February-April, 2014).

Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) Woman in an Armchair (Eva) (1913), which was recently gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art by philanthropist and cosmetics mogul, Leonard A. Lauder, is currently on view in the institution’s Lila Acheson Wing for modern and contemporary art. The painting will exhibited for three months as part of a preview of Lauder’s monumental bequest to the museum.

Lauder’s gift, which is said to be worth at least $1 billion, includes 78 Cubist paintings, drawings, and sculptures and will significantly improve the Met’s 20th century holdings. The gift includes 33 works by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), 17 by Georges Braque (1882-1963), 14 by Juan Gris (1887-1927), and 14 by Fernand Léger (1881-1955). The entire Lauder collection will be exhibited at the Met during the fall of 2014.

Woman in an Armchair (Eva) is one of Picasso’s most arresting paintings. A portrait of his mistress, Eva Gouel, the work epitomizes the Cubists’ rejection of the traditional interpretations of space, time, and perspective. The highly eroticized masterpiece was lauded by the founding father of Surrealism, André Breton (1896-1966), in his groundbreaking text Surrealism and Painting (1928).

Officials at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have announced that philanthropist and cosmetics mogul Leonard Lauder will donate $1 billion worth of art to the museum. The gift includes 78 Cubist paintings, drawings, and sculptures and will significantly improve the Met’s 20th century holdings. The Leonard A. Lauder Collection includes 33 works by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), 17 by Georges Braque (1882-1963), 14 by Juan Gris (1887-1927), and 14 by Fernand Léger (1881-1955); for a private Cubist collection it is unmatched in its quality and breadth.

Highlights from the Lauder Collection include Picasso’s landscape The Oil Mill (1909), which was one of the first Cubist images to be reproduced in Italy; Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass (1912), the first Cubist paper collage ever created; and Picasso’s Head of a Woman (1909), which is considered the first Cubist sculpture. Together, these works tell the story of a movement that transformed the landscape of modern art. Cubism departed from the traditional interpretations of art, challenged conventional perceptions of space, time, and perspective, and paved the way for abstraction, a concept that dominated the art world for much of the 20th century.

Lauder acquired his first Cubist works in 1976 and has maintained his remarkable dedication to collecting for nearly 40 years. He continues to collect and is committed to looking for new opportunities to add to his gift to the Met. In coordination with Lauder’s remarkable gift, the Met is establishing a new research center for modern art. The center is supported by a $22 million endowment that Lauder helped spearhead. Grants for the center came from various trustees and supporters of the Met, including Lauder.

The Lauder Collection will be exhibited for the first time at this Met during the fall of 2014.

The Baltimore Museum of Art has organized the first exhibition devoted to the Jewish-American artist Max Weber’s (1881-1961) formative years in Paris. Born in Russia, Weber emigrated to the United States at the age of 10. In 1905, after studying at the Pratt Institute in New York, he traveled to Paris. Weber soon became acquainted with a number of important modern artists including Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), and Henri Rousseau (1844-1910). Upon his return to New York in 1909, Weber helped introduce cubism to America.

Max Weber: Bringing Paris to New York explores Weber’s transformation from a classical painter to a bold, pioneering artist. The exhibition features over 30 paintings, prints, and drawings by Weber, many of which are on loan from the Estate of Max Weber. The show includes works by Matisse, who spent time as Weber’s instructor, Picasso, Rousseau, Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901).

Today, Weber is not the artist most readily associated with the cubist movement. However, at the peak of his career, Weber was a bona fide celebrity; in 1930 he became the first American artist to be given a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Max Weber: Bringing Paris to New York is on view through June 23, 2013.

The 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, referred to today as the Armory Show, was one of the most influential art events to take place during the 20th century. The show, which was held in New York City’s 69th Regiment Armory, introduced the American public to experimental European art movements including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. While realistic movements dominated the country’s art scene, works by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), and Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) left the Armory Show’s American visitors awestruck.

On February 17, 2013, 100 years after the Armory Show took place, the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, New Jersey presented The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913. The exhibition does more than just celebrate the significant art event; it commends the American artists who presented two-thirds of the nearly 1,200 works on view. While European art was a hugely important part of the Armory Show, The New Spirit aims to disprove the notion that the American art featured at the show was largely provincial.

The New Spirit brings together 40 diverse works of American modern art including realist works from the Ashcan School as well as more experimental pieces executed by the painters associated with the influential photographer and art dealer, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). The Montclair exhibition presents works by well-known artists such as Edward Hopper (1882-1967), William Glackens (1870-1938), Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Robert Henri (1865-1929), and John Marin (1870-1953) alongside works by lesser-known artists including Manierre Dawson (1887-1969), Kathleen McEnery (1885-1971), and E. Ambrose Webster (1869-1935). The exhibition will also feature works by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) and Matisse to illustrate the influence of European modern art on its American counterpart.

The New Spirit will be on view through June 16, 2013.

100 years after the seminal Armory Show in New York City, The Heckscher Museum of Art presents Modernizing America: Artists of the Armory Show. On view through April 14, 2013, the exhibition features works from the museum’s permanent collection and explores the show that changed the country’s perception of modern art.

Organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, the Armory Show, officially titled the International Exhibition of Modern Art, took place at the 69th Regiment Armory and introduced radical works of art to the public; a far cry from the realistic art they were accustomed to. Artists, critics, and patrons were presented with European works that boasted avant-garde sensibilities and spanned genres like Futurism, Cubism, and Fauvism. The show transformed the landscape of modern art and inspired an unmatched growth and progression in American art.

Works on view include paintings by Marguerite Zorach (1877-1968) and Arthur B. Carles (1882-1952); works on paper by Joseph Stella (1877-1946), Oscar Bluemner (1867-1938), and Charles Sheeler (1883-1965); and sculptures by artists such as Walter Kuhn (1877-1949).

The Heckscher Museum of Art was founded in 1920 by August Heckscher in Huntington, New York. The museum boasts over 2,000 works and focuses mainly on American landscape paintings as well as American and European modernism and photography.

The Vorticists, the summer exhibition at Tate Britain, opens next month: I saw the show in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation. Who were the Vorticists? Galvanic Ezra Pound was the band's vocalist, belting it out. With his ziggurat hair, he was the impresario, the excitationist, the amplificationist, just as another writer, Marinetti, was the vocal focal point of the Italian Futurists. Every movement needs a writer to whip up the manifesto. The philosopher TE Hulme was its theorist. The leading participants were expatriates – the American sculptor Jacob Epstein, the ex-Canadian Wyndham Lewis, the Frenchman Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, the American photographer-in-exile Alvin Langdon Coburn.

The movement was short-lived, barely lasting from 1914 to 1917. Epstein was never an official Vorticist. Nor was David Bomberg. But both could see the commercial point of Vorticism – the biz of the buzz. And they made a more lasting impact than various other English painters who were drawn into the Vortex – Pound's wife Dorothy Shakespear, Jessica Dismorr, Frederick Etchells, Helen Saunders, Christopher Nevinson, the Yorkshireman Edward Wadsworth, William Roberts. Apart from Roberts (barely represented here), none of these slight painters is touched with talent: they are canon fodder. They are the infantry, the grunts, bulking agent, the barium meal which creates the sense of a movement. The flush New York lawyer, John Quinn, antisemite, lover of Lady Augusta Gregory, patron of TS Eliot and the avant-garde magazine the Dial, also threw money at and down the Vortex.

And what was Vorticism? For all its international recruits, it was a parochial British attempt to emulate and excel Cubism and Futurism. Another ism. No wonder (in 1925) Hans Arp and El Lissitzky co-authored the trilingual Kunstismen (Isms in Art in English). Constructivism was set up in Russia. Fernand Léger's Tubism was just round the corner. There was Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus . . . Arp and Lissitzky don't mention Vorticism, however. Why not? Because it was effectively invisible, a variant, a hanger-on, a wannabe. Vorticism was keeping up with the Cubists. A great many of the catalogue essays here are intent on translating the art into ideology. Every picture is worth 1,000 words. Or more. And we get them. The art historians assiduously mine the art for traces of Bergson, Kant, Newton, Max Stirner, Nietzsche, Georges Sorel.

Actually, the impulse behind Vorticism, the theory, is simple. The machine is central to Vorticism. Everything was subsumed to the machine. Le Corbusier famously said in 1923 that a house was a machine for living in. By then, the idea was domesticated and cosy. In January 1914, Hulme wrote that "the specific differentiating quality of the new art [will be] the idea of machinery". It is an irony that Langdon Coburn's mechanical Vortographs – disappointing double- and triple-exposures – meant he was swiftly dumped by Pound. (Langdon Coburn's straight photograph portrait of Wyndham Lewis shows an inadvertent apostasy of vision: note the great gathering of cubist folds in Lewis's ample crotch.)

In Orlando, Virginia Woolf definitively mocked the idea that literature, that prose style, was the toy of social conditions: "Also that the streets were better drained and the houses better lit had its effect upon the style, it cannot be doubted." Apparently, Wyndham Lewis was of the opposite persuasion. Social conditioning was crucial: he is against prettiness, he favours abstraction, because "a man who passes his days amid the rigid lines of houses, a plague of cheap ornamentation, noisy street locomotion, the Bedlam of the press, will evidently possess a different habit of vision to a man living amongst the lines of a landscape". However, this glib assimilation of seeing to surroundings – falling for a formula – is effectively repudiated by Wyndham Lewis when he subsequently writes: "In a painting certain forms MUST be SO; in the same meticulous, profound manner that your pen or a book must lie on the table at a certain angle, your clothes at night be arranged in a set personal symmetry, certain birds be avoided, a set of railings tapped with your hand as you pass, without missing one." What does this mean? Lewis is invoking superstition and ritual – and the iron law of instinct.

Eliot means much the same thing when he writes, in After Strange Gods, that theories of romanticism and classicism – Eliot was a classicist – count for nothing at the moment of composition, when it is impossible "to repair the damage of a lifetime". You can read the sex manual but the warm living woman will come as a complete surprise. In art, the hand and the eye are decisive. The brain guides the eye which guides the hand. Or so we think. But frequently the chain of command is disrupted, reversed, and the mind sees what the hand has already done. We look for inevitability.

And, once or twice, we find it in this exhibition. Jacob Epstein's Rock Drill (1913-15) was reconstructed in polyester resin by Ken Cook and Ann Christopher in 1973-74. It is the exemplary Vorticist art work. It shows a man on a tripod who is one with his machine. His drill is also his rigid proboscis, his hard, angled phallus. The tripod has weights (embossed Colman Bros Ltd Camborne England) on each leg, just above midpoint – which look like enlarged joints, or a bee's pollen knee-pads (only available in black).

The rib cage of the figure is exactly like the twin cylinders on a motorbike. He is recognisably human, true, but the human body, with its curves and trim little bum, has been made-over to the angular machine: it is an armoured exoskeleton. The arms are like greaves. I thought of Seamus Heaney's description of a motorbike lying in flowers and grass like an unseated knight. And I thought too of "Not My Best Side", UA Fanthorpe's marvellous poem about Uccello's St George and the Dragon in the National Gallery. In it, Fanthorpe imagines the young girl being rather taken by the dragon's equipment, when suddenly, irritatingly, "this boy [St George] turned up, wearing machinery".

Rock Drill is a tour de force, of energy, a vibrant sculptural collage. The head is turned so we can ponder its long, insect profile. It is immensely alien and spooky, even after you realise it is a long welder's mask, untitled and initially unrecognisable, tilted but not revealing a face. There is no face. The mask is the face.

The other great work is the Frenchman Gaudier-Brzeska's Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound. No photographic reproduction prepares you for the scale of this piece. Or the satisfying solidity of the marble. In the Palazzo Guggenheim, the authorised copy was beautifully lit so the shadows were incised and the planes visible. The only thing that is Vorticist about the piece is Gaudier-Brzeska's direct carving, without prior clay models or plaster-of-Paris maquettes – an earnest of Vorticist energy, of vitalism.

|

|

|

|

|