|

Displaying items by tag: Diego Rivera

Starting January 7, 2013, Antiques Roadshow will kick-off its 17th season with three episodes filmed in Corpus Christi, Texas. While the series has a reputation for revealing hidden treasures to unassuming owners, the lost Diego Rivera painting that appears in the upcoming season is truly a rare find.

Earlier this year, Rue Ferguson inherited a painting bought by his great-grandparents in Mexico in 1920. He assumed it was worth some money, but when he took the piece to Antiques Roadshow during their stay in Corpus Christi, he was dumbfounded when he heard the painting was valued at $800,000 to $1 million.

Created by Rivera, one of the foremost Mexican painters of the 20th century, in 1904 when he was only a teenager, El Albani spent decades out of the public eye. While it is recorded in Rivera’s personal archive, the artist’s family could never locate the painting as it was hanging in Ferguson’s great-grandparents home. For nearly 30 years after Ferguson’s parents inherited the painting, they believed it to be a fake and kept it in storage. It wasn’t until the early 1980s that Ferguson’s father discovered the painting to be authentic and took it to be restored. The family donated the work to the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, TX but Ferguson asked for the painting back when he learned it was no longer on public display.

After visiting Antiques Roadshow and learning just how important a work El Abani is, Ferguson decided to look for a museum that specializes in Rivera’s work and/or Latin American art to house the historic painting.

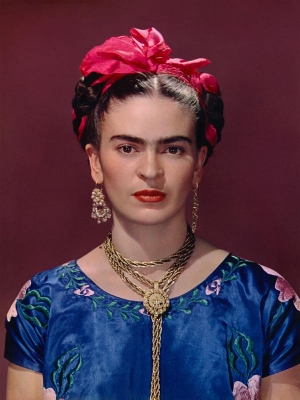

While Frida Kahlo is known for her bright and highly personal self-portraits, her role as a style icon is not to be dismissed. Most women of the 1930s embraced form-fitting dresses, coiffed hairdos, and dainty, pencil-thin eyebrows. Kahlo preferred to make appearances wearing ribbons, full skirts, bold jewelry, loose peasant blouses with vivid embroidery, and her signature untamed eyebrows.

A full collection from Kahlo’s wardrobe will go on display at the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City beginning November 22nd. Sponsored by Vogue Mexico, Appearance Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo will include jewelry, shoes, and clothes that had been locked away in the artist’s armoires for almost 50 years.

Smelling of cigarette smoke and perfume and stained from painting, Kahlo’s clothing served as an armor of sorts. Kahlo’s life was rife with pain, both emotional and physical. Polio left one of her legs thinner and weaker than the other, a bus accident maimed her when she was only 18, she suffered multiple miscarriages, and endured a tumultuous marriage with the Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. Kahlo coped with all of these experiences in her painting as well as through her dress. Her long, full skirts covered her debilitated leg and her loose blouses covered the rigid corsets she wore for back pain.

When Kahlo died in 1954, Rivera ordered that her clothes be locked up for 15 years. After his death three years later, art collector Dolores Olmedo became the manager of his and Kahlo’s houses and refuses to allow access to Kahlo’s letters, clothes, jewelry, and photographs. They were not unlocked until Olmedo’s death in 2004.

Highlights from Appearances Can Be Deceiving include the white corset Kahlo wore in the self-portrait The Broken Column and an earring that was a gift from Pablo Picasso and was featured in a self-portrait from the 1940s. The mate has not been found. A Tehuana dress, named after Indian women of that region, was Kahlo’s signature piece of clothing. Worn with large gold earrings and flowers braided into her hair, the dress is featured in many self-portraits.

In 1931, the Museum of Modern Art commissioned Diego Rivera to provide one of its galleries with five portable murals that were the subject of a five-week exhibition.

Now after 80 years in storage, the murals are being re-hung, along with three other New York-themed pieces made at the same time. “People think of this as a museum of Matisse and Picasso.

They don’t think of Rivera as a lion of the institution,” says Leah Dickerman, the curator of the department of painting and sculpture.

Considering his relative youth (he was 45 at the time), his nationality and political leanings, Rivera was a radical choice for the new institution, she says.

And so to the latest episode of the Frida and Diego telenovela. No matter that both died in the Fifties: they live on through their art and larger-than-life personae, plus the mythology that’s built up around them as two tempestuous halves of art’s most famous couple.

Our previous update came last summer, when Frida and Diego appeared on either side of Mexico’s new 500 peso bills. A quite brilliant artistic conceit on Bank of Mexico’s part, bringing the pair together yet simultaneously keeping them apart – obverse and reverse, yin and yang, sun and moon, Huitzilopochtli and Coyolxauhqui – as had so often been the case in life.

Famously, Frida and Diego couldn’t live with or without each other, their relationship marked by marriage, divorce, remarriage, tantrums, affairs (hers with Trotsky, among others; his with her sister Cristina, among others), miscarriages, abortions, accidents (a tram crash at 18 left her crippled for life), passion, patriotism, murder (Trotsky’s, most notably) and even a little art.

The soap’s latest instalment comes in Chichester, where – for the first time ever in Britain – works by both artists are showing side-by-side. The fact it includes just three or four quality Kahlos and barely one decent Rivera is neither here nor there: this is a riveting show.

Its 40 works are drawn from the collection of the late Jacques and Natasha Gelman, Eastern European émigrés who settled and married in Mexico in the Forties. In time, Natasha and Frida would become good friends, but their initial exchanges were marked by jealousy and animosity.

Rivera was then his country’s most famous artist, having pioneered the Mexican Muralist movement and painted – in praise of the Mexican revolution – endless square metres of fresco on state buildings.

At six foot and 21 stone, he was a giant in every sense, and in 1942 Jacques Gelman commissioned him to paint his wife’s portrait. The resulting canvas bursts with erotic tension. Draped immaculately in décolleté white satin, Natasha stretches out languorously on a blue sofa, like a Hollywood sex siren: she’s blonde, bejewelled and surrounded by a cornucopia of white calla lilies, as long, lithe and luxuriant as she is.

Little wonder that when Jacques asked Frida to paint her own portrait of his wife a year later, the response was far from flattering. Natasha boasts a fine fur coat, diamond earrings and freshly curled hair, yet she looks cold and distant – the epitome of Slavic sullenness and antithesis of the ever-colourful Frida. So pronounced are her curls, indeed, they resemble the horns of a ram.

|

|

|

|

|