|

Displaying items by tag: Royal Academy

An important work by American painter Benjamin West was recently installed in the McGlothlin American Galleries. The portrait was acquired during the June 18 meeting of the VMFA Board of Trustees and is among the most valuable acquisitions in VMFA history.

Benjamin West, also known as the “father of American painting,” was at one point the most prominent painter in the British Empire. He served as President of the Royal Academy, History Painter to the King, and Surveyor of the King’s Pictures until his death in 1820. While in London, he also mentored American artists Charles Wilson Peale, Gilbert Stuart, and John Trumball – each of whom is represented in VMFA’s American Galleries.

David Chipperfield has today unveiled his plans to reconfigure and renovate the Royal Academy of Arts in London, which will include building a bridge between two historic buildings.

Described by the London-based architect as "a series of subtle interventions", the development will include connecting Burlington House, the grand Palladian house used by the Royal Academy since the mid-19th century, and 6 Burlington Gardens, a former University of London building purchased by the art institution in 2001.

The Royal Academy is to present the first blockbuster of the year, and expectations are high for this exhibition of Flemish baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens – an artist who painted everything from family portraits to ceilings including at Banqueting House in Whitehall. But the artist is known for his feast of color, violence, eroticism and history that entranced the rulers who paid him to decorate palaces across early 17th-century Europe, and not least his sensuously fleshy female nudes and the term they spawned: "Rubenesque."

The artist was also a scholar, a self-made gentleman and noted diplomat who used his connections with royal patrons to broker deals on behalf of European powers. From the French Romantic painter Delacroix, whose works owe Rubens everything, to Picasso, who claimed to dislike Rubens but was obviously influenced by him, this exhibition promises to be a truly stupendous celebration of a the artist's onfluence; the exhibition will look at how Rubens has inspired of great artists during his lifetime and over the proceeding centuries.

Anselm Kiefer was born in Germany in 1945. A new life can rarely have started in a less promising place and time. To enter the world as the Third Reich fell was to be a baby surrounded by human ash.

Does that seem a tasteless way of putting it? Well, Kiefer is not tasteful. Ever since he posed for a photograph in 1969 giving the sea a Nazi salute, he has resurrected the terrors of the 20th-century in a shocking, pungent and explicit way that defies both the politeness of forgetting and the evasiveness of appropriate speech. He would rather you were angry than amnesiac. He will not let the ashes of history’s victims blow away, but thrusts them in your face as a handful of truth.

Anselm Kiefer is a bewildering artist to get to grips with. The word that comes up most often when his work is discussed is the heart-sinking and slippery "references". His vast pictures, thick with paint and embedded with objects from sunflowers and diamonds to lumps of lead, nod to the Nazis and Norse myth, to Kabbalah and the Egyptian gods, to philosophy and poetry, and to alchemy and the spirit of materials. How is one to unpick such a complex personal cosmology? Kiefer himself refuses to help: "Art really is something very difficult," he says. "It is difficult to make, and it is sometimes difficult for the viewer to understand … A part of it should always include having to scratch your head."

Now 69, Kiefer is the subject of a retrospective at the Royal Academy, where he is an honorary academician and which, through its summer exhibitions, has done much to bring him to the attention of the British public.

“I didn’t read a lot,” Dennis Hopper (1936-2010) once confessed, “but the idea of the decisive moment, catching something at a given moment, was very interesting to me.” Consequently, an unexpected presence presides over “The Lost Album,” an exhibition of Hopper photographs at the Royal Academy, London (through October 19). As you walk around, you keep being reminded of Henri Cartier-Bresson. The great Frenchman was obviously Hopper’s principle influence when he picked up a camera.

Hopper’s best images are at once formally perfect and utterly fleeting. Take his picture of Ed Ruscha — his friend and fellow artist — in 1964, for example. Ruscha, looking almost ridiculously handsome in the James Dean manner, is standing on the street in Los Angeles. Behind him is a window through which a neon sign reads “TV Radio Services.” Mirrored in the glass of the window are the road and the buildings on the other side of the street.

A collection of rarely seen works by Marc Chagall have gone on show in London for the first time.

The 26 works, which include paper gouaches and oil paintings, span Chagall’s career from 1913 to 1984, showcasing the Russian-French artist's distinctive folk-inspired, playful style.

None of the paintings were exhibited in the recent Chagall retrospective at Tate Liverpool last year, with just “Dos a dos” having been on show before to the British public at the Royal Academy in 1985.

The communications revolution changed everything, including art: a statement that was just as true in 1514 as it is 500 years later. What transformed the world back then was printing, and some of the results are on view in “Renaissance Impressions: Chiaroscuro Woodcuts From the Collections of Georg Baselitz and the Albertina, Vienna” (Royal Academy, London until June 8). They are as beautiful as they are unfamiliar.

George Bellows and the American Experience is currently on view at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio. The exhibition highlight’s the Columbus Museum’s significant Bellows collection, which is widely recognized as the best in the world. The show also includes a number of paintings on loan from other museums and private collections.

Born and raised in Columbus, Ohio, George Bellows moved to New York City in 1904 to study with the influential artist and teacher, Robert Henri, and soon became the youngest member of the Ashcan School. Dedicated to chronicling the realities of day-to-day life, Bellows made a name as the boldest of the Ashcan artists. He was recently the subject of a major retrospective, which included his well-known paintings of boxing matches and gritty New York tenements, many of which came from the Columbus Museum.

Melissa Wolfe, the Columbus Museum of Art’s Curator of American Art, said, “For the past year our Bellows paintings have traveled the world as part of a major retrospective that drew crowds to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Royal Academy in London. We’re excited to welcome them home and to be able to celebrate the profound impact George Bellows had, and continues to have, on the art world.”

An international scholarly symposium will be held on November 8 and 9, 2013 to complement the exhibition. George Bellows and the American Experience will be on view at the Columbus Museum of Art through January 4, 2014.

Opening on October 2, 2013 at Tate Britain in London, Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm will be the first exhibition to explore the history of physical attacks on art in Britain from the 16th century to the present day. The show will present famously marred works while exploring the religious, political and aesthetic motives that have provoked these violent acts.

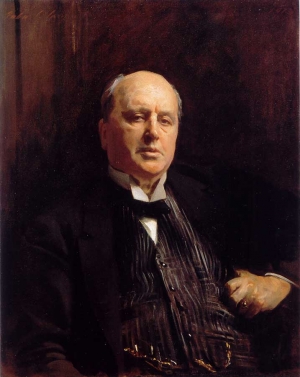

The exhibition will include Statue of the Dead Christ (1500-20), which is being loaned to the Tate by London’s Worship Company of Mercers where the work was discovered beneath the chapel floor in 1954. The work was attacked by Protestants during the Reformation and is missing a crown of thorns, arms and lower legs. It is the first time that the Mercer has loaned the work since it was discovered nearly 60 years ago. John Singer Sargent’s (1856-1925) portrait of Henry James, which was attacked by a suffragette at the Royal Academy in 1914 with a knife, will also be on view. A less violently disgraced work is a portrait of Oliver Cromwell that was hung upside down by a devote monarchist. The work is on loan from the Inverness Museum in Scotland.

Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm will be on view at Tate Britain through January 5, 2014.

|

|

|

|

|