|

Displaying items by tag: Money

David Hickey, one of America’s foremost art critics is known for his acerbic commentary, but his latest tirade against the world of modern art is downright scathing. Hickey, a professor, curator, and author, told the Observer that he will be walking away from contemporary art, a genre he says has been ruined by rich collectors who are more concerned with money and celebrity than quality.

Hickey claims that art editors and critics have lost their edge, spending more time catering to the wealthy people who hold the reigns on the contemporary art market than surveying the actual work (which he says is also lacking). Hickey is not alone in this claim. A number of contemporary art curators, museums, and galleries have deemed the work of such artists as Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Antony Gormley bloated and empty – the result of too much fame and not enough criticism. While the notion of the artist as celebrity is not new, today’s market is saturated with it and gaining status has taken precedence over making revolutionary, ground-breaking art.

A former dealer, Hickey is attuned to considering art in monetary terms but his objections stem from his belief that contemporary art has become too broad, too elitist, and lacks discretion. Hickey’s retirement will remove an important critical voice from the equation. He plans to complete a book on the pagan roots of America, aptly titled Pagan America, as well as a book of essays titled Pirates and Framers.

The Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.’s oldest art museum, has been losing money for years and is currently in need of at least $130 million in renovations. The only major museum on the Mall that is privately owned, times have been tough for the Corcoran who must charge admission and raise large amounts of money to survive. Attendance has dropped drastically and donations to the museum have roughly halved since the recession.

The Corcoran’s commanding Beaux Arts façade and top-notch collection of 17,000 works including pieces by Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet, and Willem de Kooning are simply not a big enough draw to keep the institution afloat, especially when every other institution on the Mall offers free admission. The Corcoran’s board of trustees are currently debating between a number of options to keep the museum active including selling the current building, combining forces with another institution, and moving out of the city.

While many find the loss of the Corcoran will leave the Washington Mall with a gaping hole, the museum announced that they have been discussing possible solutions with the National Gallery of Art, George Washington University, and a few other unnamed institutions. The Corcoran hired a real estate firm as its adviser in September and hopes to have its future mapped out by the first half of 2013.

The District of Columbia Historic Preservation League is looking to extend the landmark designation for the Corcoran’s exterior and interior. If the institution were approved, any major construction would be subject to public review.

As all the talk of record prices demonstrates, contemporary art has soared in value over the last 10 years, outperforming stocks as an investment and drawing attention to possible bonanzas to be found in the market.

But not all boats have lifted with the tide.

Prices for the work of a variety of artists, including some top names like Larry Rivers, Eric Fischl and Francesco Clemente, have declined or stayed flat at auction in recent years, according to data compiled by Artnet, a company that tracks such sales.

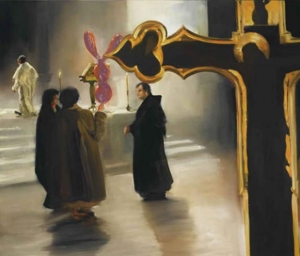

For example, a Dutch Masters painted cigar box, created by Rivers and valued as high as $40,000 last year, sold in September for less than $4,000. Last month Mr. Fischl’s untitled painting of robed figures in a church sold for $194,500, $70,000 less than it fetched six years ago.

And Mr. Clemente’s “Parabola,” a painting Sotheby’s had valued as high as $90,000 a year ago, sold for a third of that in March. Often these are temporary descents. Other works by these artists can still command hefty prices. A Clemente painting estimated at $30,000 to $50,000 at auction this spring sold for $76,900.

Nonetheless, at a time when so much attention is paid to skyrocketing values, the dreary performance of some artists’ portfolios is a topic seldom broached.

“We in the auction business want to put our best foot forward, so when we get a good price, we make a big fuss about it,” said Elaine Stainton, the director of the painting department at the auction house Doyle New York. “When we have a disappointing sale, we keep our mouths shut.” Perhaps nothing in the art world is as mystifying to the layman as the often abrupt changes in works’ values. The market’s overall ups and downs make sense. And it seems logical that works by old masters act like stable blue-chip stocks, while contemporary art functions like growth stocks: volatile but with a sudden capacity to crown genius and create fortune.

But how to explain the cruel backslide of artists whose work escalates, then slips in value? Just as it is difficult to pinpoint precisely why work by some artists rises in value, experts say it can be harder still to explain why some artists’ value declines.

“There is a constant ebb and flow in art historical reputations,” said Jeffrey Deitch, a longtime New York gallery owner who now directs the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. “The reputation of even the greatest figures like Picasso are in flux.”

Certainly the value of an individual work of art can be affected by its size (bigger is better), condition, provenance and how recognizable it is, something often referred to as wall power.

Andy Warhol, for example, is a premium name brand. This month a silk-screened Warhol self-portrait touched off a bidding war at Christie’s before selling for $38.4 million, well above its high estimate of $30 million. “Some people like that instant recognizability, that someone can walk into the living room and say, ‘That’s a Warhol,’ ” said Mary Hoeveler, an art adviser in New York.

When the recession forced museums to cut back on expensive loan shows a few years ago, some worried that it would hurt attendance: With great works from around the world replaced by stuff hauled up from storage rooms, would art lovers’ hearts still flutter?

Now, though, many museum directors are finding virtue in necessity. Shows built largely from in-house collections have drawn well, they say, and curators are introducing the public to unsung treasures.

“If the recession has compelled us as museums in this country to focus even more intensely than we have in the past on our collections, that’s a good thing,” said Glenn D. Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art. “Because they’re our primary responsibility.”

Last year, for example, the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition on Picasso, stocked completely from the museum’s own holdings, drew 700,000 visitors. And when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art opened its Resnick Pavilion last fall, it celebrated by showcasing its new collection of early European fashions.

“The public doesn’t care whether you own it or borrow it,” said Michael Govan, the director of that Los Angeles museum. “They’re just interested in the presentation and the content.”

|

|

|

|

|