|

Displaying items by tag: Florence

Is it possible that the apotheosis of Western sculpture was achieved over 2,000 years ago and it’s been all downhill since then? A new blockbuster exhibit, ‘Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World,’ strongly buttresses this view.

Greek bronzes hold a rarified place in the art world, both in terms of quality and scarcity. Most Greek sculpture that has survived is carved from marble. In ancient times, however, bronze was more highly prized and served as the material of choice for the wealthiest patrons and most skilled artists.

Florence officials ordered the closure of many of the Tuscan city's museums on Friday, including the famed Uffizi Gallery, while technicians checked for damage after a particularly violent storm.

The museums house some of the greatest treasures of the Renaissance and the Uffizi is home to masterpieces by Fra Angelico, Boticelli, Raphael and others.

Michelangelo's famous statue of the biblical figure David is at risk of collapse due to the weakening of the artwork's legs and ankles, according to a report published this week by art experts.

The findings, which were made public by Italy's National Research Council, show micro-fractures in the ankle and leg areas.

The "David" statue dates from the early 16th century and is housed in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence. The results of the report were published this week in the Journal of Cultural Heritage, a publication devoted to research into the conservation of culturally significant works of art and buildings.

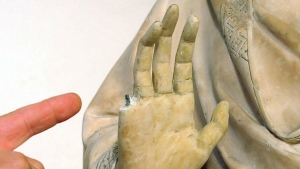

An American tourist broke a finger off of a 600-year-old statue housed in Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, which boasts a significant sculpture collection dating from the Renaissance and medieval periods. The damaged statue, which is thought to depict the Virgin Mary and dates from either the 14th or 15th century, is part of a work titled Annunciazione. The sculpture is believed to be by the Florentine sculptor Giovanni d’Ambrogio.

The tourist, a 55-year-old man from Missouri, allegedly snapped off the right pinky finger of the statue while attempting to measure it. While the incident appears to have been an accident, Italian officials questioned the American and will determine what action to take. It is unclear how much it will cost to fix the finger, which was not original to the work and was added to the sculpture at some point after its completion.

Tim Verdun, the director of the museum, said that “in a globalized world like ours, the fundamental rules for visiting a museum have been forgotten, that is: Do not touch the works.”

French president Francois Hollande has given special allowance to Édouard Manet’s (1832-1883) Olympia (1863), permitting the masterpiece to travel from Paris to Venice for an exhibition. It will be the first time the influential painting has left the French city since it was given to the nation in 1890. Olympia, which features a nude woman and her fully clothed maid, shocked audiences with its subject’s provocative gaze and the suggestion that she was a prostitute.

Olympia, which is part of the Musée d’Orsay’s collection, will travel to Italy to anchor an exhibition at the Doge’s Palace in Venice. The painting will appear alongside Titian’s (1485-1576) The Venus of Urbino (1538), which is on loan from Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, as part of the exhibition Manet: Return to Venice. The exhibition features 70 works including 42 paintings by Manet on loan from the Musée d’Orsay, which will received a considerable amount in fees for the unprecedented loan. A number of paintings will also be on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Manet: Return to Venice will explore how Italian artists such as Vittore Carpaccio (1460-1520), Antonello da Messina (1430-1479), and Lorenzo Lotto (1480-1556) influenced the French painter. The exhibition will be on view from April 25 to August 4, 2013.

As part of a yearlong celebration of Italian culture hosted by Italy’s foreign minister, Michelangelo’s (1475-1564) iconic work, David-Apollo, will be go on view today at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Minister Giulio Terzi di Sant’Agata unveiled the sculpture yesterday, December 12. David-Apollo will be on view in the West Building’s Italian galleries through March 3, 2013.

Michelangelo carved David-Apollo in 1530 for Baccio Valori, who served as the interim governor of Florence per the Medici pope Clement VII’s appointment. Michelangelo and the pope were at political odds, but the artist wished to make peace with the Medici through his work. Michelangelo never finished David-Apollo as he left Italy and never returned after Clement VII’s death.

Part of the Museo Nazionale del Barello’s collection in Florence, David-Apollo traveled to the National Gallery once before in 1949. The masterpiece’s installation in Washington over sixty years ago coincided with former president Harry Truman’s inaugural reception and attracted more than 791,000 visitors. In 2013, David-Apollo’s presentation will coincide with President Barack Obama’s inauguration.

The Year of Italian Culture, launched by Sant’Agata under the auspices of the President of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, will bring a range of Italian masterpieces to nearly 70 cultural institutions across the United States. Works range from classical and Renaissance to baroque and contemporary and cover the realms of art, music, theater, cinema, literature, science, design, fashion, and cuisine.

We are brought up to think that when we have earned leisure and rest ... we may go forth and cross oceans and mountains and see on Italian soil the primal substance, the Platonic ‘idea’ of our consoling dreams and richest fancies.” Writing this in 1877, Henry James conjured the spell that Italy cast on his compatriots.

With the end of the civil war, the American dream could begin. Yet industrialisation was eating into the wilderness. Those of an artistic sensibility felt battered by what James described as “our crude and garish climate, our silent past, our deafening present”. Rooted in a classical past yet racing towards an avant-garde future, Europe beckoned like a promised land.

For would-be painters of modern life, Paris was the Mecca. The timeless, melancholy magic of Venice was also seductive. Yet the high drama of these cities discomfited too. When the US exiles longed for refuge, it was to Florence they turned, a city “without commerce, without other industry than the manufacture of mosaic paper-weights ... with nothing but the little unaugmented stock of her medieval memories, her tender-coloured mountains, her churches, palaces, pictures and statues”, according to James.

A band of artists, mainly from New England, took up residence in villas overlooking the city. With its flower-filled gardens and sunlit olive glades, the landscape, so much more civilised than the great American wilderness, was an idyllic spot in which to practice the en plein air style they had learnt from the impressionists. Supplementing their colony was an Anglo-American literary elite including Bernard Berenson, Edith Wharton and James.

This exhibition shines a spotlight on those who either lived or passed through the Tuscan capital in the decades before the first world war. But the sprinkling of household names – John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt, Frederick Childe Hassam, Thomas Eakins and James McNeill Whistler – were never permanent residents: Florence, as James noted, was a city where “by eight o’clock at night, apparently, everyone had gone to bed”. It lacked the cosmopolitan oomph to make it a cradle of the avant-garde and the paintings by those who did settle there, such as Frank Duveneck and his wife, Elizabeth Boott, lack the bold conviction and groundbreaking technique of works by their more famous peers.

Last weekend, at this time of intense financial crisis and economic uncertainty, I found myself addressing some of Europe's most important money men. The occasion was a conference organised by the Palazzo Strozzi Foundation, entitled Finance and the Arts: Where is the Florence of the 21st Century? We were in the Palazzo itself, described by the director of the museum it now houses as the Trump Tower of the 15th century.

Beyond the big windows on the fifth floor, the sun was setting over the most picturesque panorama imaginable: the Florentine campanili sloping down to the Arno, encircled by pinkish Tuscan hills.

My duty was to talk about the show I had co-curated, Money and Beauty: Bankers, Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities. All the same, it's hard to pass up an opportunity to say something pertinent when, for the only time in your life, you have in front of you such people as the governor of the Bank of England, the chairman of Lloyds TSB and similarly important figures from the ECB, the Federal Reserve and the Swiss National Bank, not to mention 70 or so hedge-fund managers, entrepreneurs, policymakers, academics, curators, art dealers, artists and collectors.

If we wish to understand, I began, why the banking families of 15th-century Florence financed such an extraordinary flowering of the finest art, we have to take seriously the enemies of banking, and, above all, the church's ban on all interest-bearing loans – something the theologians called usury, and believed ran contrary to God's natural law. Why? Because making money from loan interests involved a renunciation of honest toil and a refusal of the trade and social position you were born into. The banker/usurer, and quite probably the borrower, too, was trying to hurry up the social scale. It was socially disruptive. Chaos would surely ensue.

All this seems naive to us. We cannot believe a rigid social hierarchy is ordained by God, or its preservation in anyone's interest but that of the privileged folk at the top. But there is more: the moneylender, as the church saw him, was inevitably an obsessive and conflicted person. "Thus the usurer," complains Bernardino of Siena, "always at first Mass kissing saints' feet and burning candles under their noses. He comes early because he can't sleep for hankering after money."

The church had understood that when financial deals become complex ("money copulating on money") then the mind locks into the process, it grows excited, it can't sleep. If people can change their status by dint of playing with money, they will think of nothing else. Then they hurry to mass because they don't want others to realise what mental condition they're in.

The artists of 15th-century Florence didn't depict usurers. Nobody wanted to go there. But the Flemish painters of the 16th century interpreted the church's position well enough. Switching on PowerPoint, I showed my bankers Quentin Metsys's The Usurers, where spiritual ugliness is stamped on miserly faces as surely as the king's head on a coin. Even more provocative is Marinus van Reymerswaele's The Money Lender and His Wife. Here the man and woman are attractive, ordinary people like you and me. But their attention is entirely captured by the gold coins they are counting. They relate to each other through money, not touch or conversation. And their hands are tense and claw-like. "Remember well, oh usurers," St Anthony of Padua had preached a couple of centuries before, "that the devil has possessed your hands that they might not do charitable works".

It was the Renaissance bankers' fear of this obsession, and the social stigma that might ensue, that turned their minds to charity and penitential gestures. Having developed the art of commerce-linked currency exchanges into a lucrative form of derivative – to avoid making straight loans – they were never sure whether they were usurers or not. So they restored churches, commissioned devotional paintings, and, in so doing, discovered beauty and demonstrated that they were not merely money men to be defined and summed up by their account books.

The morning after my talk, the conference proper began. Seventy of us sat in concentric circles, provided with electronic voting devices that enabled us to express our views on such questions as, "Will the west remain the dominant force in world art markets?"; 44% thought it would, 37% that it wouldn't.

Florence, 24 June (AKI) - Italy has launched a campaign to convince the Louvre Museum in Paris to lend the Mona Lisa painting to Florence's Uffizi Gallery in 2013 to mark the 100th anniversary of its recovery following one of history's most famous art thefts.

The Italian Culture Ministry and the Province of Florence have jointly launched an appeal to the French to lend them what may be the world's most famous masterpieces, but the prestigious French museum said the painting is not in the condition to withstand the trip south.

Leonardo Da Vinci's Mona Lisa was briefly displayed in the Uffizi in 1913 after being recovered in a Florence hotel two years after its theft from the Louvre.

That was the last time it appeared in Italy and only one of three times the work was displayed outside of the Louvre, according to a statement posted on Thursday on the Province of Florence website.

Starting with Italian politicians, the initiative aims to collect at least 100,000 signatures to be sent to France in around six months, the statement said.

|

|

|

|

|